This is the chance for eligible fresh fruit and vegetable growers to recover some of their expenses for implementing food safety practices on their farms.

For 2025:

- Application is due between January 1, 2025 and January 1, 2026

- Eligible expenses must be between January 1, 2025 and December 31, 2025

Eligible specialty crop operations can apply for Food Safety Certification for Specialty Crops (FSCSC) by working directly with the Farm Service Agency offices at your local FSA office for details. Applications will be accepted via mail, fax, hand delivery, or electronic means.

How the Food Safety Certification for Specialty Crops Program Works

The FSCSC program provides financial assistance for specialty crop operations that incur eligible on-farm food safety program expenses related to obtaining or renewing a food safety certification in 2025. This program helps offset costs to comply with regulatory requirements and market-driven food safety certification requirements. FSCSC will cover a percentage of the specialty crop operation’s cost of obtaining or renewing their certification, as well as a percentage of their related expenses.

Program Eligibility

Eligibility requirements for FSCSC applicants are outlined below. We recommend you review these requirements before initiating your FSCSC application.

To be eligible for FSCSC, an applicant must:

- Have obtained or renewed: 2025 food safety certification issued during the calendar year.

- Be a specialty crop operation (growing fresh fruits and vegetables); and meet the definition of a small business or medium size business.

- A small (farm) business means an applicant that had an average annual monetary value of specialty crops the applicant sold during the 3-year period preceding the program year of not more than $500,000.

- A medium (farm) business means an applicant that had an average annual monetary value of specialty crops the applicant sold during the 3-year period preceding the program year of at least $500,001 but no more than $1,000,000.

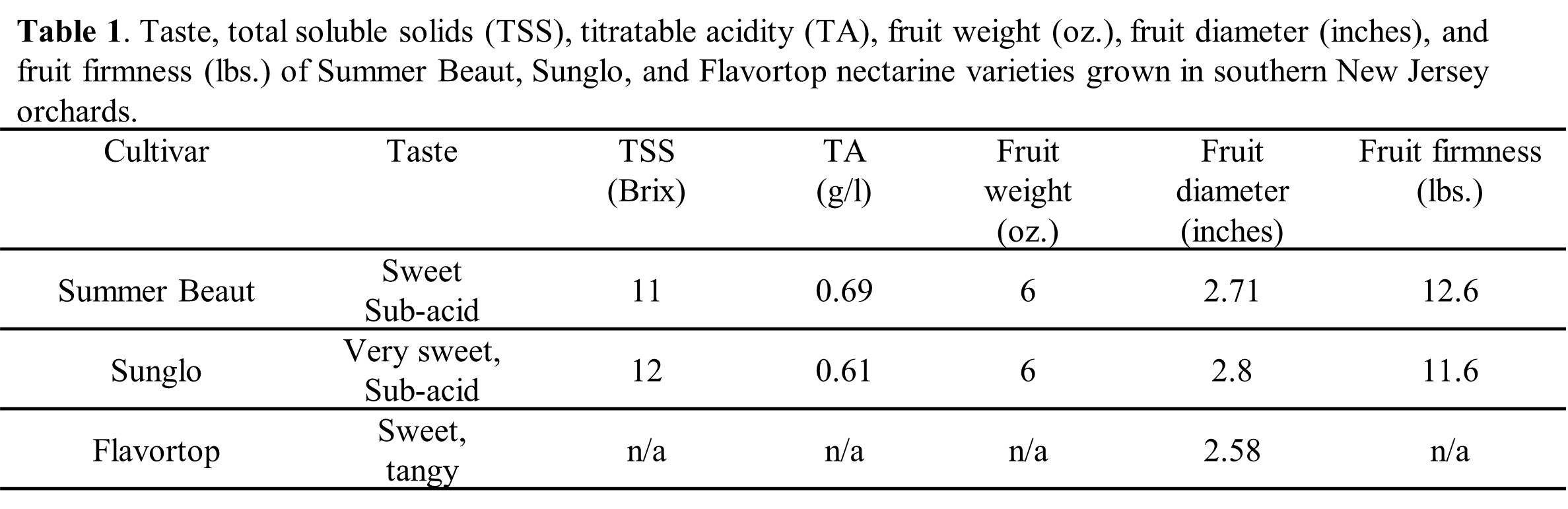

| Category of Eligible Expenses | Payment Amount of Eligible Costs |

| Developing a Food Safety Plan for First Time Certification | 75% (no maximum) |

| Maintaining or Updating a Food Safety Plan | 75% up to $675 |

| Food Safety Certification | 75% up to $2,000 |

| Certification Upload Fees | 75% up to $375 |

| Microbiological Testing of Produce | 75% up to 5 tests |

| Microbiological Testing of Soil Amendments | 75% up to 5 tests |

| Microbiological Testing of Water | 75% up to 5 tests |

| Training Expenses | 100% up to $500 |

FSCSC payments are calculated separately for each category of eligible costs based on the percentages and maximum payment amounts. The FSCSC application and associated forms are available online at farmers.gov/food-safety.

You are encouraged to contact the Farm Service Agency office about FSCSC, program eligibility, or the application process. You may also call 877-508-8364 to speak directly with a USDA employee ready to provide one-on-one assistance.

For food safety resources, information on the Food Safety Modernization Act and third party audits go to Rutgers On-Farm Food Safety