The Northeast Cover Crops Council will host a fall webinar series. The webinars will take place from 12-1 pm on Wednesdays from October 1 to November 5, 2025. Click here to register for the series. [Read more…]

Vegetable Crops Edition

Seasonal updates and alerts on insects, diseases, and weeds impacting vegetable crops. New Jersey Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations updates between annual publication issues are included.

Subscriptions are available via EMAIL and RSS.

Quick Links:

NJ Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations

NJ Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations

Rutgers Weather Forecasting - Meteorological Information important to commercial agriculture.

Rutgers Weather Forecasting - Meteorological Information important to commercial agriculture.

Veg IPM Update 9/12/25

Greetings from the Veg IPM team!

Sweet Corn

Corn is wrapping up very slowly with the cool weather we’re having. Meanwhile, corn earworm (CEW) moth captures are staying high — many locations need 3-day spray intervals (see map). If temperatures get high (>85 degrees F), shorten the spray interval by one day. Rotation is important for avoiding resistance, and there are four IRAC groups that are registered in silking sweet corn: 1 (carbamates), 3 (pyrethroids), 5 (spinosyns), and 28 (diamides). CEW is at least partly resistant to several pyrethroids, so a spray program should not rely solely on pyrethroids, although they can be useful in tank-mixes or as pre-mixed products, such as Besiege or Elevest (Group 28 + Group 3). For detailed information about resistance and potential spray programs, the University of Delaware has an excellent resource on corn earworm management.

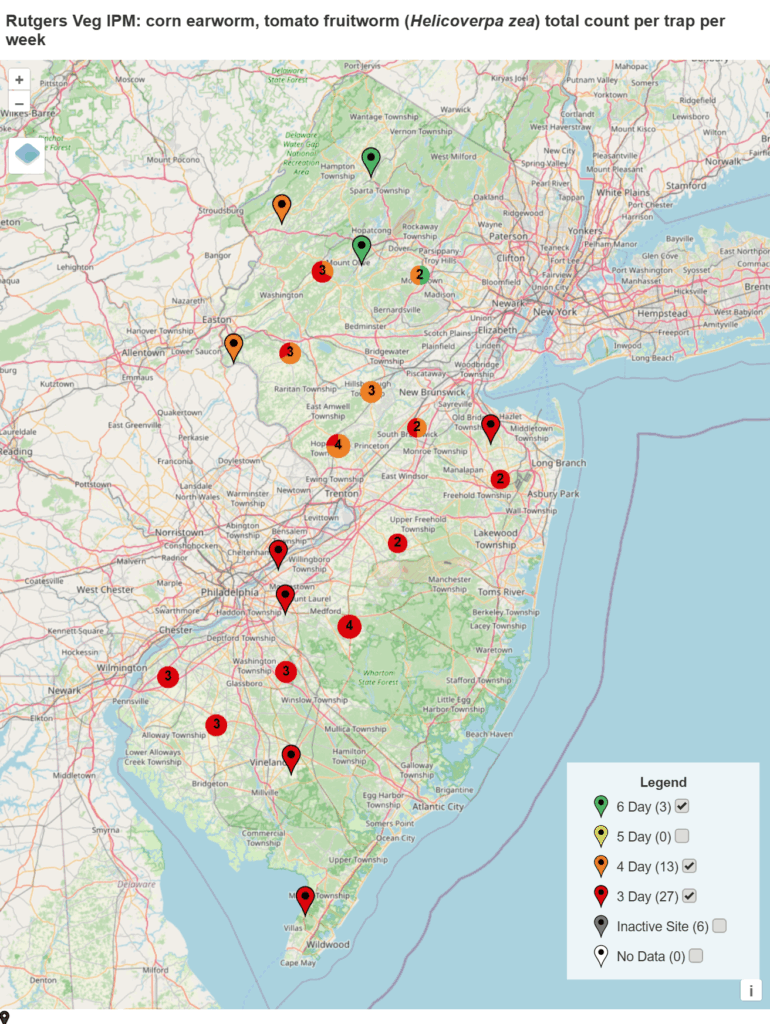

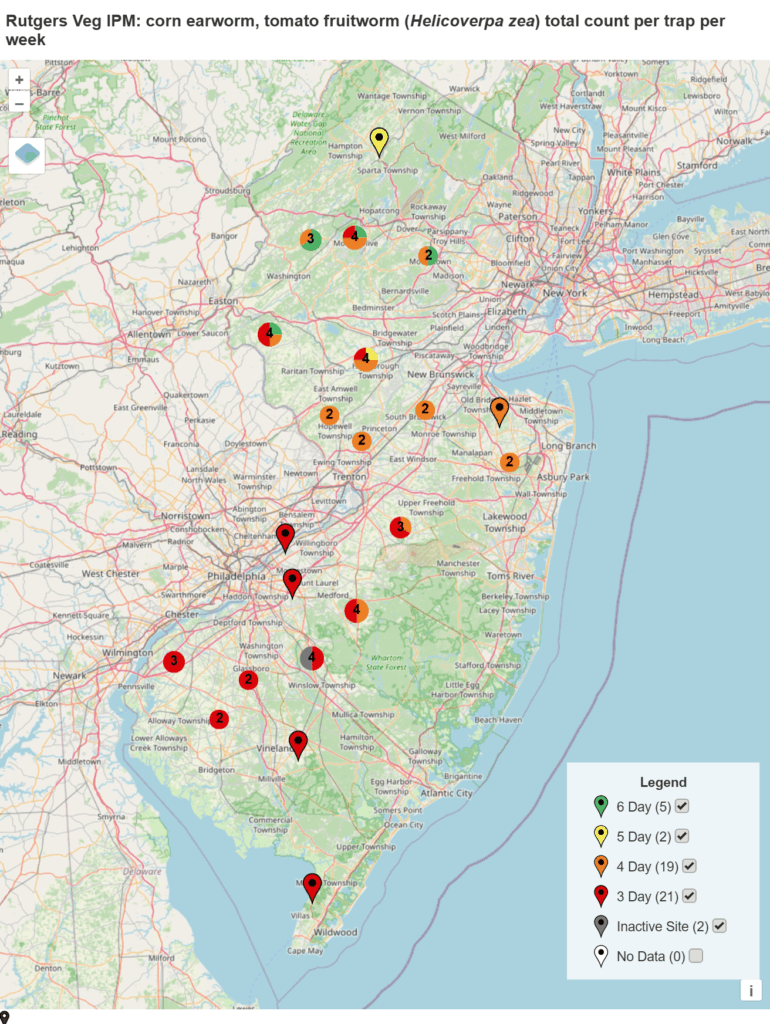

Spray intervals based on nightly pheromone moth captures for the southern part of New Jersey. Note that not all locations in the IPM program are currently trapping. This map is based on the following thresholds: 0 moths = 6-7 day schedule, 1 moth = 5 day spray schedule, 2-20 moths = 4 day spray schedule, 20+ moths = 3 day spray schedule.

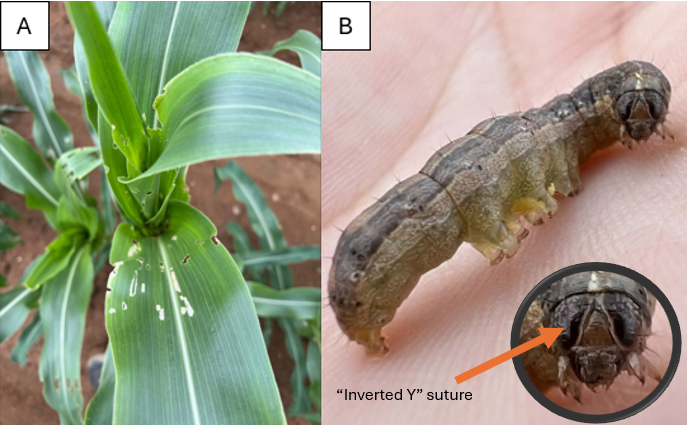

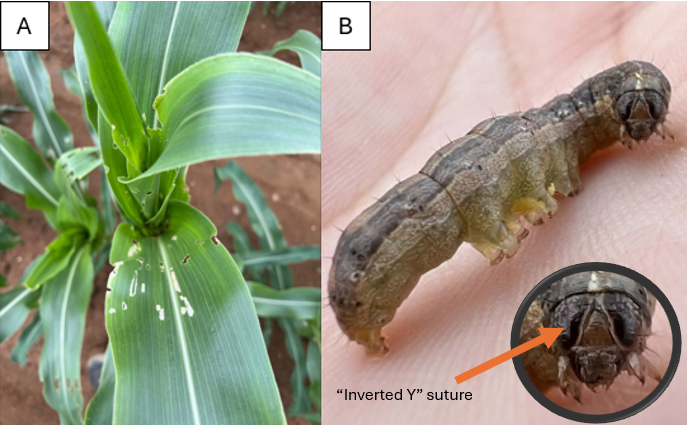

We’re seeing fall armyworm (FAW) infestations in many locations. Young larvae will cause damage known as “window paning”, in which the top surface of the leaf is eaten away, leaving behind thin, white, membranous-looking scratch marks. As the larvae get bigger, these feeding marks become more ragged (A). The damage can look somewhat similar to European corn borer feeding, but FAW damage will be more severe and will lead down into the whorl. The caterpillars have a dark head capsule with a distinct, inverted Y-shaped suture (B). They can also be identified by four dark dots arranged in a square on their last segments. We use a treatment threshold of 12% fresh feeding damage in pre-tassel corn. Below this level, treatments for FAW are unlikely to pay off and can flare up aphids. For treatment, we recommend using products other than diamides (IRAC Group 28) when treating whorl-stage infestations, as diamides are important to save for silk protection. Effective products include Lannate (Group 1A), Radiant (Group 5), Intrepid (Group 18), Intrepid Edge (5+18), and Avaunt (Group 22). Note that Avaunt can only be used through tassel push.

Fall armyworm damage (A) and larva (B). Note the distinctive suture on the head, which will differentiate FAW from other caterpillar pests of corn. Photos by Amanda Quadrel

We continue to see corn leaf aphids in sweet corn tassels and ears. In high numbers they can reduce pollination or cause honeydew and sooty mold on ears that harm marketability. Broad spectrum insecticides, especially pyrethroids, can flare up aphids by disrupting the natural enemies that typically control them. We have seen several instances where FAW sprays in the vegetative stage may have caused high aphid populations during silking. If you’re seeing a lot of aphids on corn tassels, you can start your CEW spray rotation with Lannate (group 1A), which has some efficacy for aphids. Come back a week later and check ear tips for aphid populations. If they are high, as in the below picture, use a product more targeted for aphids, such as Assail 30SG or 30 SC (group 4A), Transform WG (group 4C), or Sivanto Prime (group 4D). Keep in mind that Transform WG and Sivanto Prime have 7 day PHIs.

Corn leaf aphids on the tip of an ear. Note blue-green color with dark tail pipes (also called cornicles), legs, and antennae. Picture by Maria Cramer.

Tomatoes

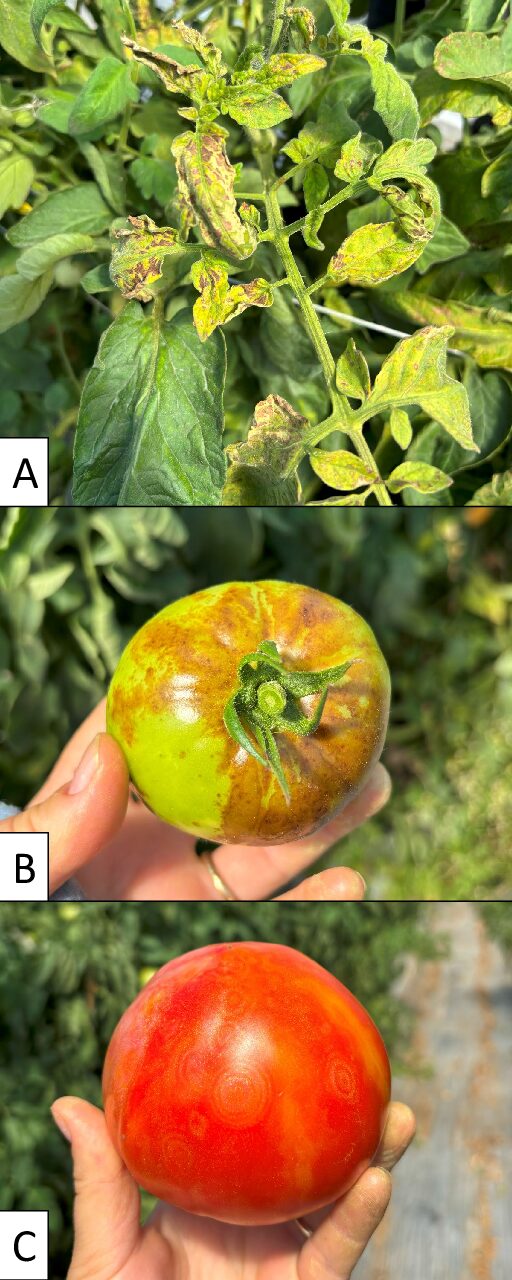

Thrips are starting to slow down as tomatoes are slowing down, but they’re still out there. Thrips management is especially important because of their ability to vector tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), a growing problem in New Jersey where we have resistance-breaking strains. There have been many outbreaks of TSWV (in both peppers and tomatoes) throughout south Jersey this season. Scouting and roguing out these plants (see pictures below) while continuing to manage thrips can help contain losses. Additionally, follow best management practices for reducing TSWV risk throughout the season.

For scouting, we consider 1-5 thrips on 10 leaves to be a low count and more than 5 thrips a high count. Other guides suggest a treatment threshold of 3-5 thrips per flower or the presence of stippling damage on fruit. Western flower thrips, the primary vector of TSWV, has resistance to some carbamates (group 1A) and organophosphates (group 1B) as well as pyrethroids (group 3), so few are useful for management. They are also broad-spectrum and hard on natural enemies, potentially flaring up secondary pests like spider mites. The following products have varying efficacy for western flower thrips management:

- Group 5 insecticides (e.g. Radiant, Entrust) historically have given the best control, but growers have been finding resistance throughout south Jersey. If you have applied Radiant or Entrust and have not gotten good control, your local thrips populations may be resistant. Group 5 insecticides can also only be used twice per season in a planting.

- Lannate (Group 1A) gives the next best thrips knockdown, but is broad spectrum and is not a part of all growers’ spray programs.

- Beleaf 50SG (Group 29) can be very effective applied through drip irrigation, but takes a while to decrease thrips populations. It is systemic, making it safer for natural enemies than some other products.

- Group 28 products with the active ingredient cyantriniliprole (e.g. Minecto Pro, Verimark, Exirel) provided suppression in trials.

- Movento (Group 23, active ingredient spirotetramat) — provided suppression in trials.

- Requiem EC (no group, active ingredient Chenopodium extract) — provided suppression in trials.

Many products only suppress thrips, meaning they kill larvae but not adults, or kill only the active life stages (larvae and adults, not the egg or pupal stages). Rotate between active ingredients and try to avoid getting to very high thrips numbers which are more difficult to knock back down.

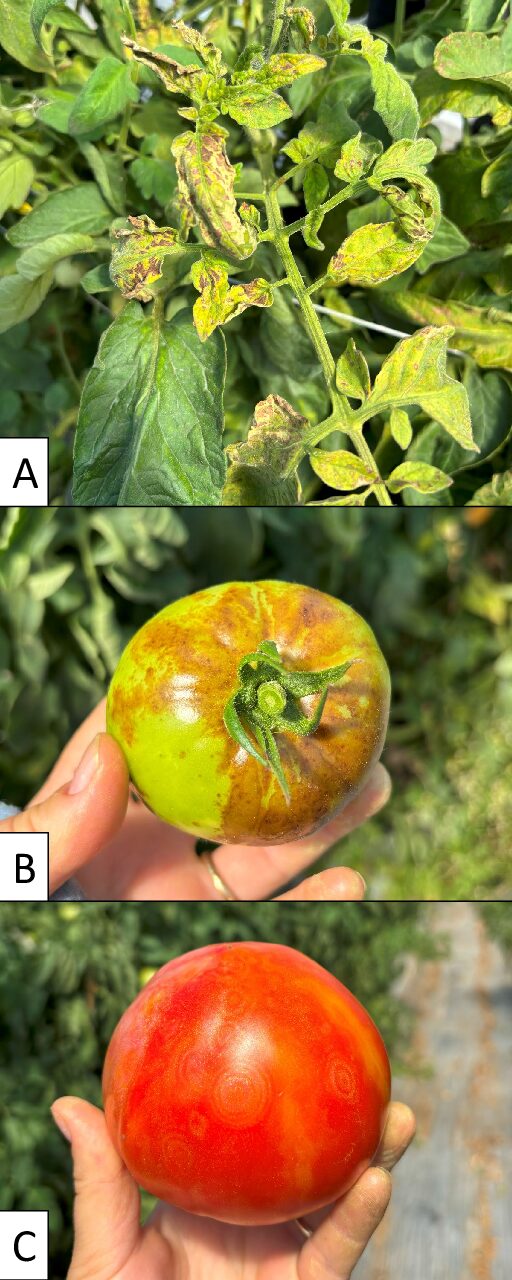

A) TSWV symptoms on leaves — note curling, yellowing, and browning. B) Symptoms on green fruit — irregular brown blotches and misshapen fruit. C) Symptoms on red fruit — concentric circles. Photos by Maria Cramer.

We’ve seen some fruit damage from caterpillars, and tomato fruitworm (AKA corn earworm), armyworms (beet and yellow striped), and hornworms on plants and fruit. There are no reliable thresholds for determining when to spray for these caterpillar pests, however scouting and consulting the corn earworm pressure map for the state will help give a sense of risk to the crop. When corn earworm pressure indicates a 3 or 4 day spray interval in corn (2-20 moths per night) as is currently the case in much of the state, tomatoes should be scouted weekly for feeding damage. Beet armyworm moth numbers in traps in Salem and Cumberland counties have been low (>5 per night). Pyrethroid resistance is widespread in tomato fruitworm/corn earworm and beet armyworm, so other classes of insecticides should be used if management is needed.

Tomato fruitworm/corn earworm infesting a green tomato. Photo by Maria Cramer.

We continue to see high spider mites in many plantings. Spider mites tend to be worse in hot, dry conditions, and their populations can dramatically increase following broad-spectrum insecticides, which reduce their natural enemies. The first sign of their presence is often light-colored stippling seen on the top surface of tomato leaves. The mites causing this damage are usually found on the undersides of leaves, though with bad infestations mites will be found on the upper surface as well. When sampling spider mites, check 10 upper leaflets in at least 5 sites per field. The treatment threshold is 2 mites per leaflet on average (one of the individual leaves that makes up the compound tomato leaf). On farms where crop rotation is limited and the same miticides have been used for multiple years we’re seeing some miticide resistance — check whether and application has decreased mite populations, and if it did not work well, do not keep using it. Rotate between miticides and only treat when above threshold. Some products for spider mites in tomatoes include:

- Nealta (group 25)

- Oberon (group 23)

- Portal (group 21A)

- Agri-Mek (group 6) *7 day PHI

- Kanemite (group 20B)

- Acramite (group 20D) *3 day PHI

Spider mite stippling visible when looking at tomato leaves from above. The spider mites are generally found on the undersides of the leaves. Photo by Maria Cramer.

Peppers

In terms of most insect pests, peppers have been looking very good. We have seen aphids, spider mites, and thrips at low levels so far, however it’s important to keep in mind that thrips can transmit TSWV to peppers as well, and so monitoring and staying on top of thrips populations is crucial. As with tomatoes, finding and roguing out infected plants is important as well (see picture below for symptoms on foliage and fruit).

A) TSWV symptoms on pepper foliage — note mottling and cupping of the foliage. B) Symptoms on cherry pepper fruit. Photos by Maria Cramer.

As a reminder, we have found pepper weevils on pepper weevil traps in Gloucester, Cumberland, and Salem Counties this summer. Read more about pepper weevil biology and management here. If you think you may have pepper weevil on your farm or are interested in monitoring, please contact Maria Cramer.

Cole Crops

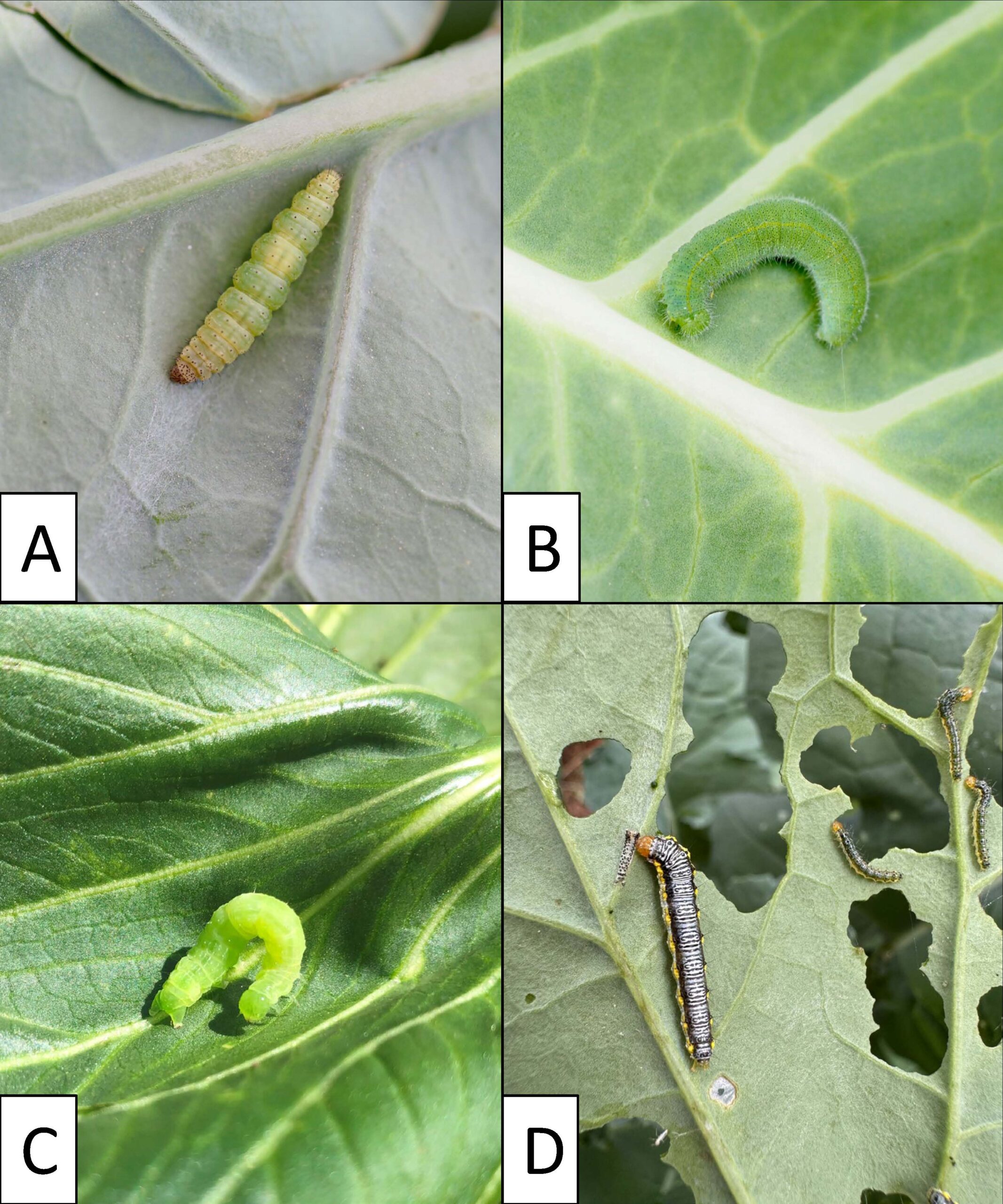

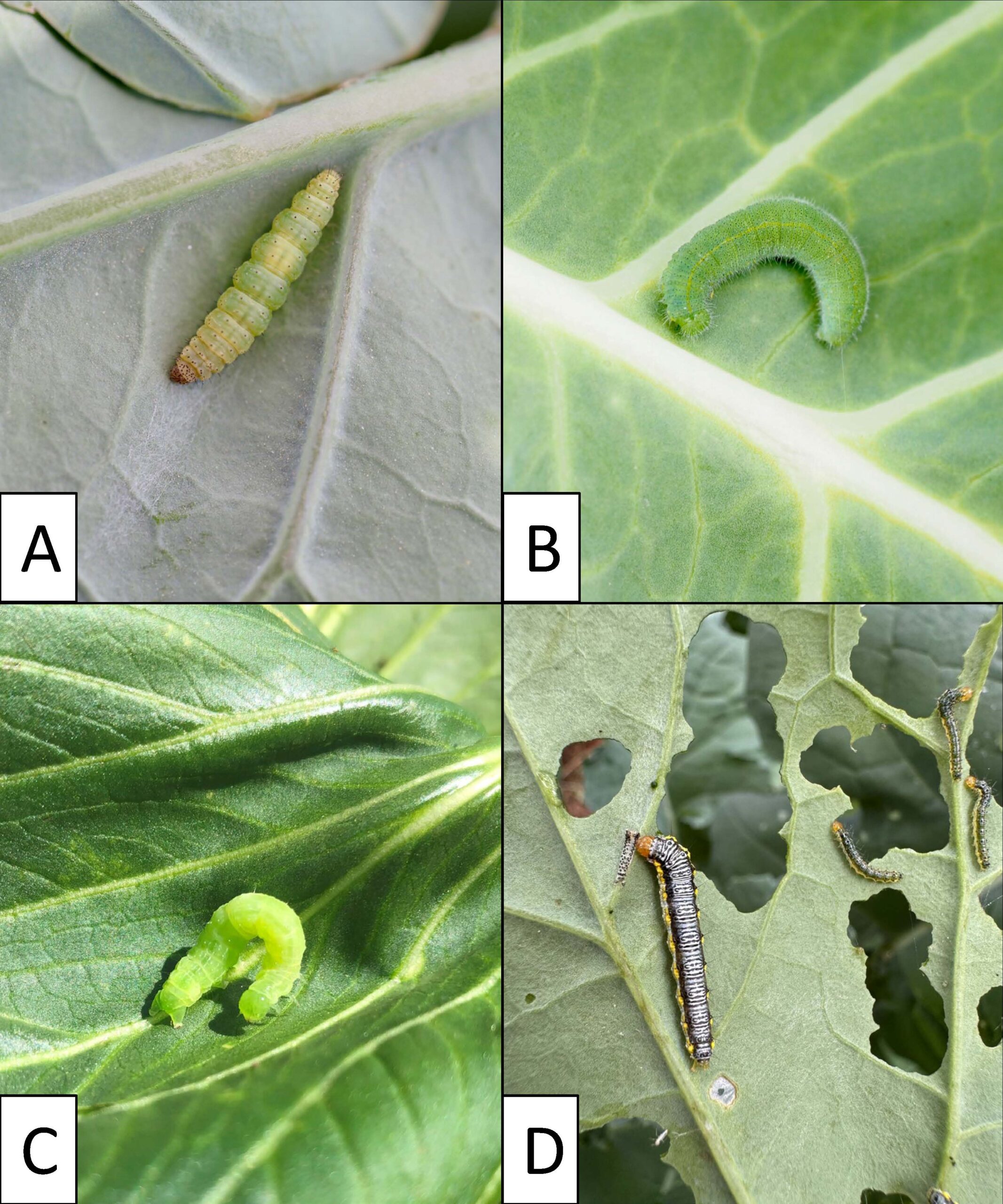

We are seeing many different kinds of caterpillars in fall cole crop plantings, including diamondback moth, imported cabbage worm, cabbage looper, cross-striped cabbageworm, and yellow striped armyworm. All cole crop seedlings can tolerate up to 10% infestation for these caterpillar. For heading cole crops between early vegetative and cupping, the treatment threshold is 30%. As heads form, the treatment threshold goes down to just 5% infestation. Sprayable Bt products (IRAC 11A) such as Dipel, Xentari, or Javelin can be effective on young imported cabbage worm, cross-striped cabbageworm, and yellow-striped armyworm caterpillars. Diamondback moth has resistance to many insecticide groups, and pyrethroids (IRAC 3A) and Bt products (IRAC 11A) are not effective for their management. Besides Bt, materials approved for caterpillar control include Entrust/Radiant (IRAC 5), Proclaim (IRAC 6), Torac (IRAC 21A), and Exirel (IRAC 28). For Bt products and contact insecticides, coverage on the undersides the leaves is essential.

Caterpillar pests of cole crops. A) Diamondback moth — smooth and tapered at each end. B) Imported cabbageworm — fuzzy and not tapered. C) Cabbage looper — characteristic looping behavior. D) Cross-striped cabbage worm — distinctive stripes, usually occurs in groups. Photos A-C by Maria Cramer, photo D from iNaturalist COO.

Downy mildew is showing up in cole crops. This is a disease that develops best around 50-59ºF and our cool night temperatures are making prime conditions for disease development. Downy mildew may appears as light-colored lesions on the top of the leaves and as masses of white spores on the lower surface. Scout at least 25 plants per field (5 plants in 5 locations), checking the undersides for spores. If you have downy mildew, rotate or tank-mix chlorothalonil 6F (FRAC M05) with another product listed in the Mid-Atlantic Veg Guide for downy mildew in cole crops, rotating MOAs. Use overhead irrigation at times of the day when leaves can dry quickly to slow disease progression.

Downy mildew spore masses on the underside of a collard leaf. Photo by Renee Carter.

Pumpkins and Other Cucurbits

Cucurbit downy mildew was first reported on 7/11/25 on cucumbers in central NJ and has been found on cucumbers and cantaloupe at the Snyder Research Farm in Pittstown. Growers should be applying protectants on cucumbers and cantaloupes for cucurbit downy mildew at this time. As of this post, we still haven’t found any instances of the disease on pumpkins, squash, or watermelon. For information on how to build an effective cucurbit down mildew control program, please reference this post by Dr. Andy Wyenandt and consult the Mid-Atlantic Production Guide for additional materials that can be used.

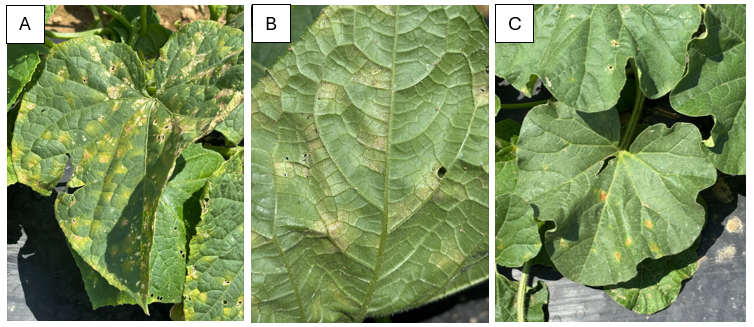

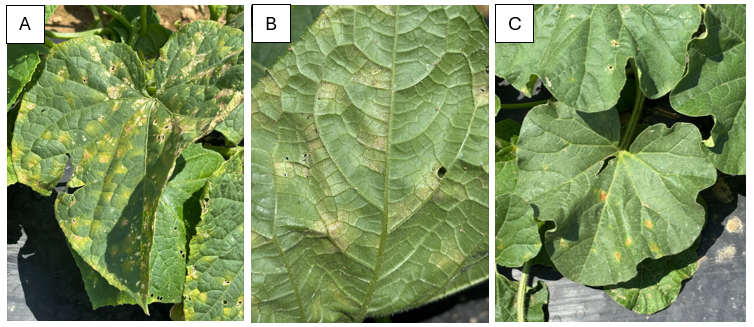

Cucurbit downy mildew symptoms on the upper surface (A) and underside (B) of cucumber leaves and symptoms on cantaloupe (C). Photos by Amanda Quadrel

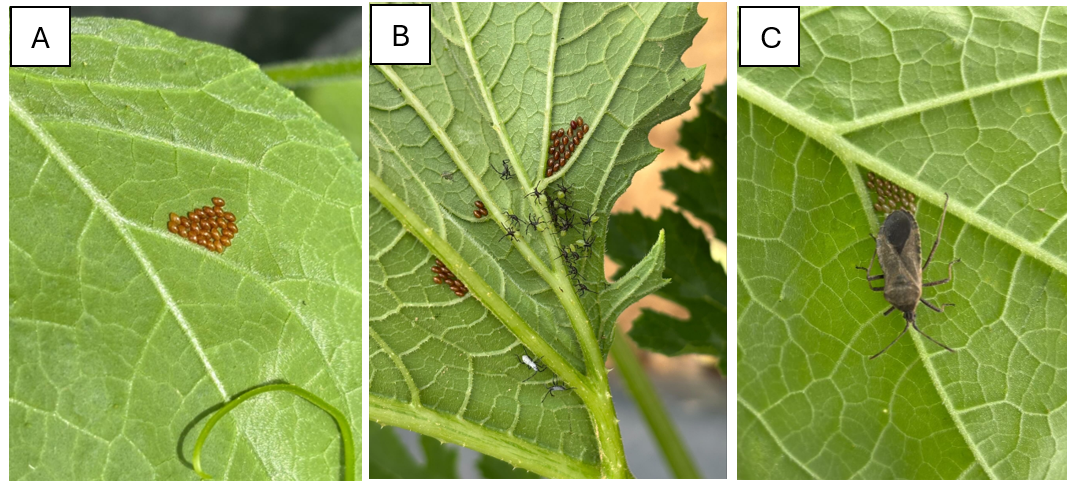

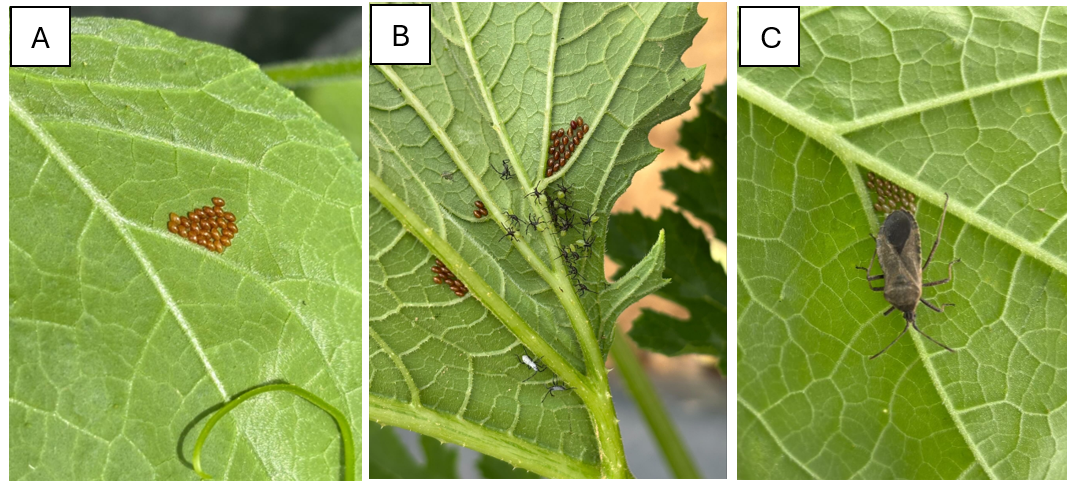

In pumpkins, we continue to see squash bug eggs and nymphs. Consider treating for squash bug if you see more than one egg mass or group of nymphs per plant (see photos below).

Squash bug eggs (A), newly hatched nymphs (B), and an adult (C). Photos by Amanda Quadrel

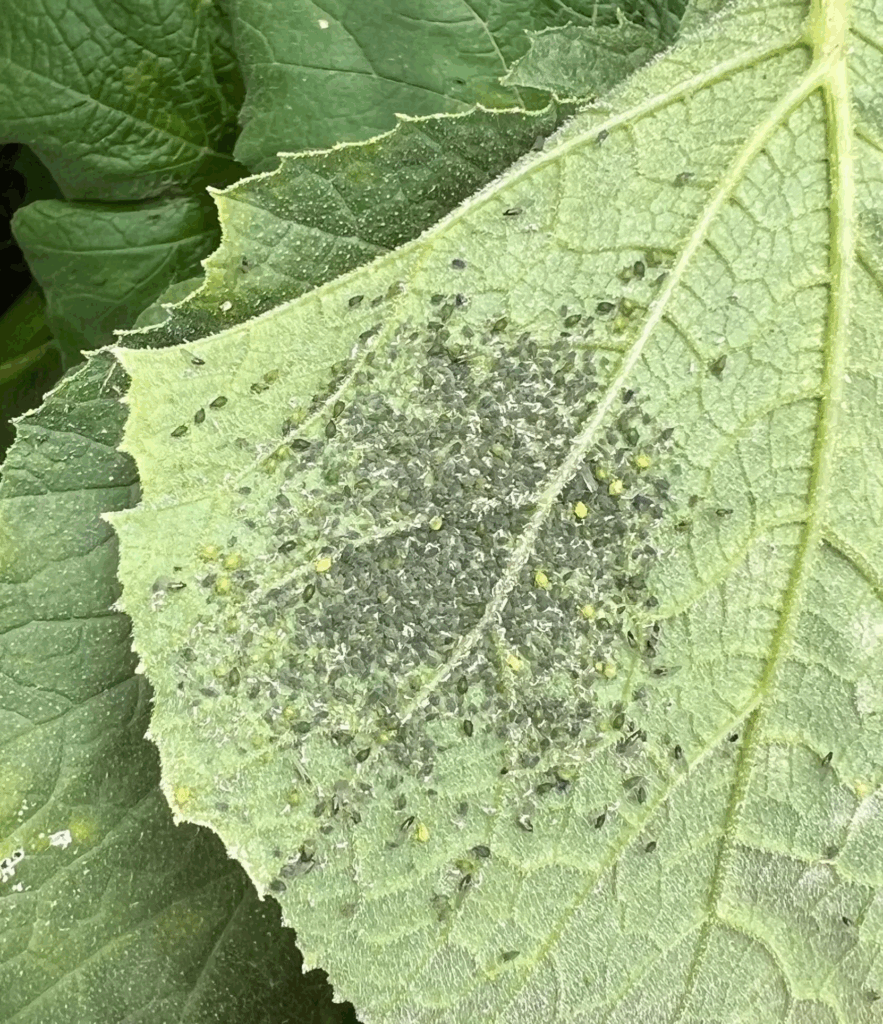

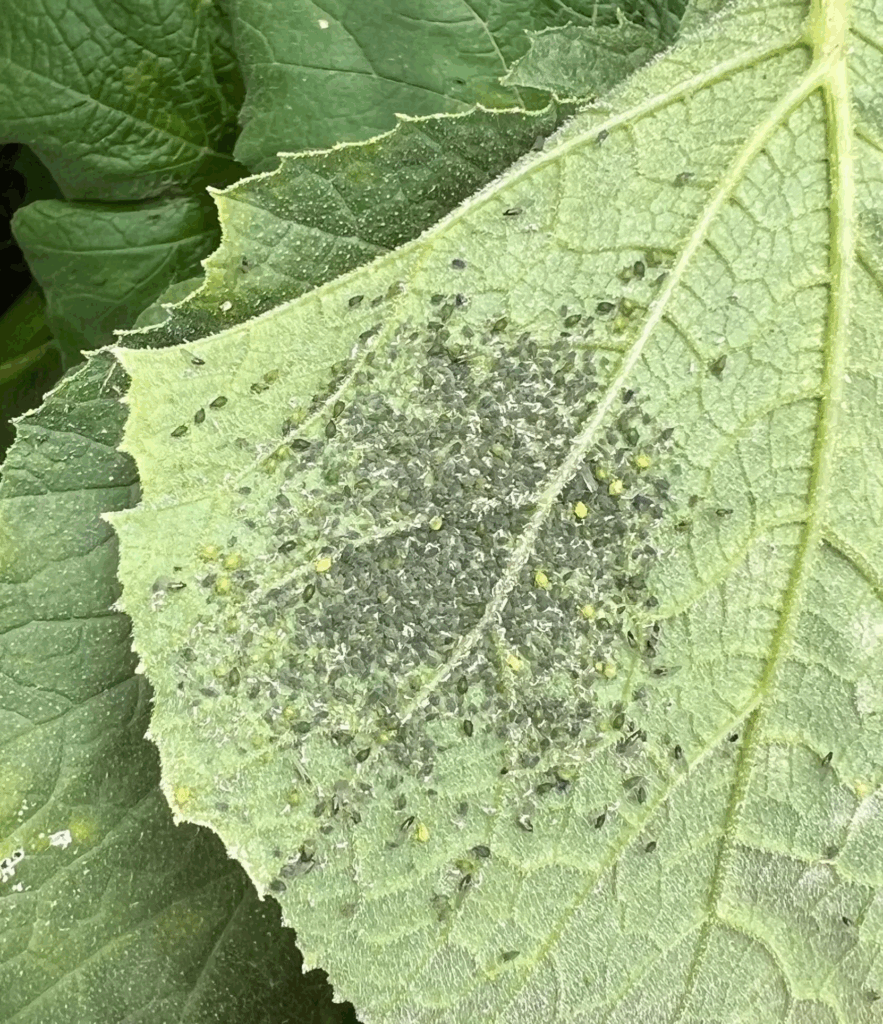

Aphid populations remain present in several scouted fields. While not causing direct damage to the fruits, the honeydew produced by aphids can stick to the fruits and attract hornets or promote sooty mold growth, resulting in unsightly fruit. If a colony is found at three or more sites in a ten site sample, growers may wish to apply control measures. There are several options available, such as Assail, Fulfill, PQZ, Sefina, and Beleaf that are labeled for aphids and are safer for bees. If also dealing with heavy mite populations, Minecto Pro can target both pests, but has a higher toxicity to bees.

Melon aphids infesting a pumpkin leaf. Photo by Amanda Quadrel.

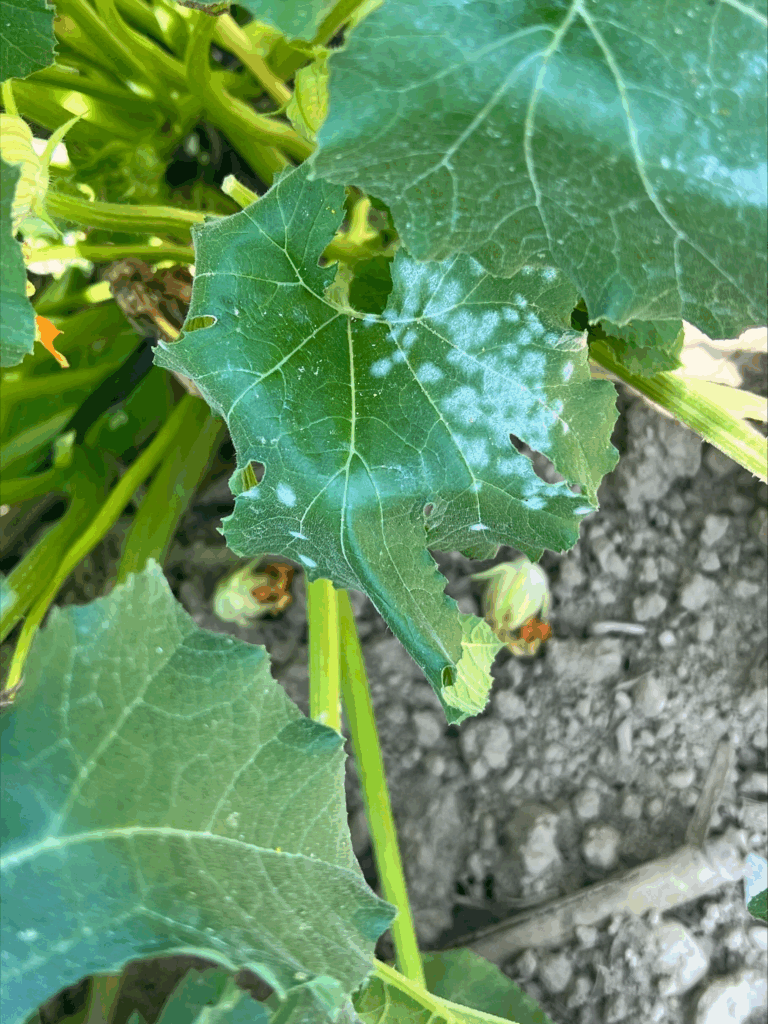

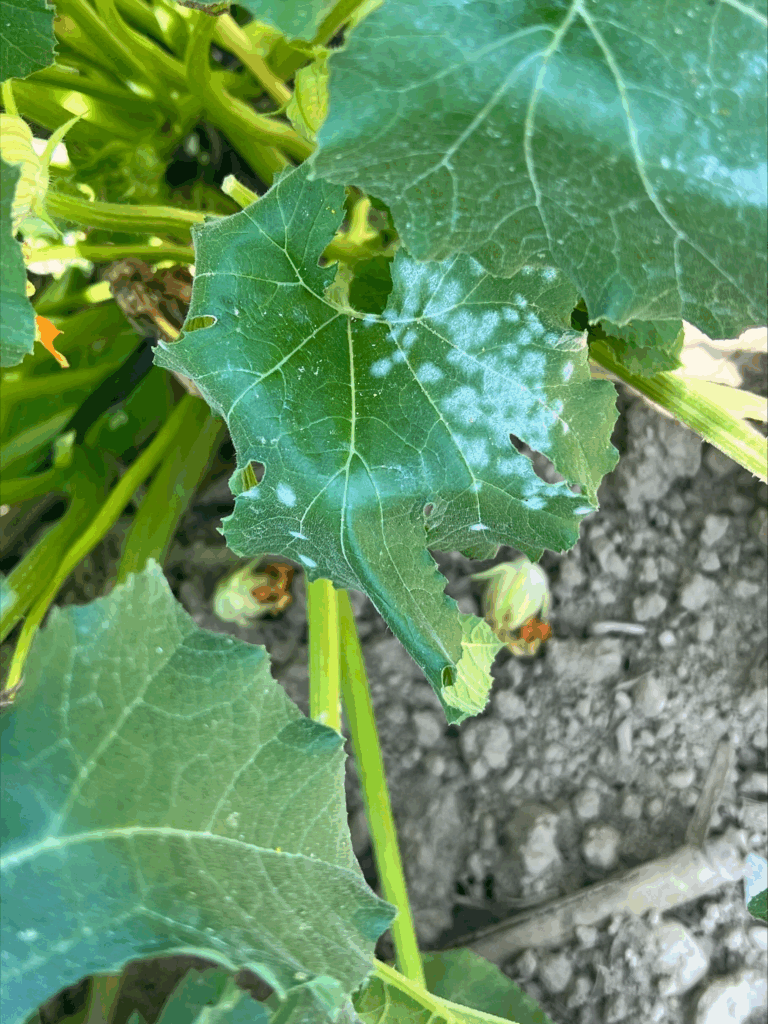

Powdery mildew has shown up in most scouted sites. If more than one leaf in a 50 leaf sample is infected, fungicide programs for powdery mildew should be initiated.

Powdery mildew on pumpkin leaf. Photo by Amanda Quadrel.

In many pumpkin fields, disease management has shifted from foliage to fruit — plan to use a high water volume in sprays if a lot of foliage remains so that sprays can contact fruit sufficiently. A preventative diseases management plan based on recommendations from the Mid-Atlantic Production Guide is important for suppressing many of these diseases. If you suspect diseases in your pumpkins (or other cucurbits), reference the “Diagnosing important diseases in Cucurbit crops” guide or send/bring samples to Rutger’s Plant Diagnostic Lab.

As always, please consult the Mid-Atlantic Commercial Vegetable Production Guide for a comprehensive list of materials that are labeled for specific crops and pests. As always, be sure to follow label rates and application instructions.

The Vegetable IPM Program wishes to thank the following Field Technicians, without whom much of the information presented weekly here would not be available.

Southern team: Renee Carter and Kris Szymanski

Northern team: Martina Lavender, Coco Lin, and Cassandra Dougherty

Networks to Reduce Risk: Annie’s Project – Info session

The program, “Networks to Reduce Risk: Annie’s Project Builds Viable Farms in Urban and Rural NJ” will include four unique field trips and a dynamic, six-part webinar series. The overarching goal of this program is to improve risk management strategies of urban and rural farm business owners by connecting them with interactive educational opportunities, practical resources, and each other. This program is open to all.

Interested participants can attend an upcoming informational session to learn more about the program objectives and activities, the expected benefits for participants, and receive information about program registration. The informational session will be held online via Zoom on Wednesday, September 24, 2025, from 7:00 pm to 8:00 pm. To register for the informational session, please visit go.rutgers.edu/ntrrinfosession. Registration is required.

All questions can be directed to anniesproject@njaes.rutgers.edu.

This work is supported by the Northeast Extension Risk Management project award no. 2024-70027-42540, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Thank you so much in advance!

Fall Vegetable Twilight Meeting on 9/18, Registration Closes 9/12

A fall vegetable twilight meeting will be held at Norz Hill Farm & Market, LLC., 120 S Branch Rd, Hillsborough Township, NJ 08844 (Somerset County) on Thursday, September 18. Registration is required and closes Friday, September 12. To register, complete this registration form or call the RCE Somerset County office at 908-526-6293 ext. 4.

AGENDA

4:00 pm – 4:15 pm Welcome, load wagons, wagon ride to field

4:15 pm – 4:45 pm Drone Seeding Winter Cover Crops into Pumpkin

Peter Nitzsche, Agricultural Agent , Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Morris County

4:45 pm – 5:15 pm Small Farm Robotic Equipment for Weed Control in Vegetable Production

Thierry Besançon, Extension Specialist – Weed Science for Specialty Crops , Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station

5:15 pm – 5:45 pm Vegetable IPM Program Update

Amanda Quadrel, Sr. Program Coordinator – Vegetable IPM, Rutgers Cooperative Extension

5:45 pm – 6:15 pm Update On Important Diseases in Vegetable Production

Andy Wyenandt, Extension Specialist – Vegetable Pathology , Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station

6:15 pm – 6:20 pm Wagon ride to tent

6:20 pm – 6:30 pm Meal of pizza and salad, provided by Vegetable Growers Association of New Jersey

6:30 pm – 7:00 pm Worker Protection Standard: Checklist for Compliance

Kate Brown, Agricultural Agent , Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Somerset County

MEETING CO- SPONSORED BY THE VEGETABLE GROWERS ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY

Pesticide Recertification Credits approved: CORE (1), 1A (3), 10 (2), and PP2 (3)

Questions? Email Kate Brown, Agricultural Agent with RCE Somerset County, at kbrown@njaes.rutgers.edu.

Veg IPM Update 9/5/25

Greetings from the Veg IPM team!

Sweet Corn

Corn earworm (CEW) moth captures are very high — many locations need 3-day spray intervals (see map). If temperatures get high (>85 degrees F), shorten the spray interval by one day. Rotation is important for avoiding resistance, and there are four IRAC groups that are registered in silking sweet corn: 1 (carbamates), 3 (pyrethroids), 5 (spinosyns), and 28 (diamides). CEW is at least partly resistant to several pyrethroids, so a spray program should not rely solely on pyrethroids, although they can be useful in tank-mixes or as pre-mixed products, such as Besiege or Elevest (Group 28 + Group 3). For detailed information about resistance and potential spray programs, the University of Delaware has an excellent resource on corn earworm management.

Spray intervals based on nightly pheromone moth captures for the southern part of New Jersey. Note that not all locations in the IPM program are currently trapping. This map is based on the following thresholds: 0 moths = 6-7 day schedule, 1 moth = 5 day spray schedule, 2-20 moths = 4 day spray schedule, 20+ moths = 3 day spray schedule.

We’re seeing fall armyworm (FAW) infestations in many locations. Young larvae will cause damage known as “window paning”, in which the top surface of the leaf is eaten away, leaving behind thin, white, membranous-looking scratch marks. As the larvae get bigger, these feeding marks become more ragged (A). The damage can look somewhat similar to European corn borer feeding, but FAW damage will be more severe and will lead down into the whorl. The caterpillars have a dark head capsule with a distinct, inverted Y-shaped suture (B). They can also be identified by four dark dots arranged in a square on their last segments. We use a treatment threshold of 12% fresh feeding damage in pre-tassel corn. Below this level, treatments for FAW are unlikely to pay off and can flare up aphids. For treatment, we recommend using products other than diamides (IRAC Group 28) when treating whorl-stage infestations, as diamides are important to save for silk protection. Effective products include Lannate (Group 1A), Radiant (Group 5), Intrepid (Group 18), Intrepid Edge (5+18), and Avaunt (Group 22). Note that Avaunt can only be used through tassel push.

Fall armyworm damage (A) and larva (B). Note the distinctive suture on the head, which will differentiate FAW from other caterpillar pests of corn. Photos by Amanda Quadrel

We continue to see corn leaf aphids in sweet corn tassels and ears. In high numbers they can reduce pollination or cause honeydew and sooty mold on ears that harm marketability. Broad spectrum insecticides, especially pyrethroids, can flare up aphids by disrupting the natural enemies that typically control them. We have seen several instances where FAW sprays in the vegetative stage may have caused high aphid populations during silking. If you’re seeing a lot of aphids on corn tassels, you can start your CEW spray rotation with Lannate (group 1A), which has some efficacy for aphids. Come back a week later and check ear tips for aphid populations. If they are high, as in the below picture, use a product more targeted for aphids, such as Assail 30SG or 30 SC (group 4A), Transform WG (group 4C), or Sivanto Prime (group 4D). Keep in mind that Transform WG and Sivanto Prime have 7 day PHIs.

Corn leaf aphids on the tip of an ear. Note blue-green color with dark tail pipes (also called cornicles), legs, and antennae. Picture by Maria Cramer.

Tomatoes

Throughout New Jersey we’re continuing to see high thrips counts both in tunnels and in the field. Thrips management is especially important because of their ability to vector tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), a growing problem in New Jersey where we have resistance-breaking strains. There have been many outbreaks of TSWV (in both peppers and tomatoes) throughout south Jersey this season. Scouting and roguing out these plants (see pictures below) while continuing to manage thrips can help contain losses. Additionally, follow best management practices for reducing TSWV risk throughout the season.

For scouting, we consider 1-5 thrips on 10 leaves to be a low count and more than 5 thrips a high count. Other guides suggest a treatment threshold of 3-5 thrips per flower or the presence of stippling damage on fruit. Western flower thrips, the primary vector of TSWV, has resistance to some carbamates (group 1A) and organophosphates (group 1B) as well as pyrethroids (group 3), so few are useful for management. They are also broad-spectrum and hard on natural enemies, potentially flaring up secondary pests like spider mites. The following products have varying efficacy for western flower thrips management:

- Group 5 insecticides (e.g. Radiant, Entrust) historically have given the best control, but growers have been finding resistance throughout south Jersey. If you have applied Radiant or Entrust and have not gotten good control, your local thrips populations may be resistant. Group 5 insecticides can also only be used twice per season in a planting.

- Lannate (Group 1A) gives the next best thrips knockdown, but is broad spectrum and is not a part of all growers’ spray programs.

- Beleaf 50SG (Group 29) can be very effective applied through drip irrigation, but takes a while to decrease thrips populations. It is systemic, making it safer for natural enemies than some other products.

- Group 28 products with the active ingredient cyantriniliprole (e.g. Minecto Pro, Verimark, Exirel) provided suppression in trials.

- Movento (Group 23, active ingredient spirotetramat) — provided suppression in trials.

- Requiem EC (no group, active ingredient Chenopodium extract) — provided suppression in trials.

Many products only suppress thrips, meaning they kill larvae but not adults, or kill only the active life stages (larvae and adults, not the egg or pupal stages). Rotate between active ingredients and try to avoid getting to very high thrips numbers which are more difficult to knock back down.

A) TSWV symptoms on leaves — note curling, yellowing, and browning. B) Symptoms on green fruit — irregular brown blotches and misshapen fruit. C) Symptoms on red fruit — concentric circles. Photos by Maria Cramer.

We’ve seen some fruit damage from caterpillars, and tomato fruitworm (AKA corn earworm), armyworms (beet and yellow striped), and hornworms on plants and fruit. There are no reliable thresholds for determining when to spray for these caterpillar pests, however scouting and consulting the corn earworm pressure map for the state will help give a sense of risk to the crop. When corn earworm pressure indicates a 3 or 4 day spray interval in corn (2-20 moths per night) as is currently the case in much of the state, tomatoes should be scouted weekly for feeding damage. Beet armyworm moth numbers in traps in Salem and Cumberland counties have been low (>5 per night). Pyrethroid resistance is widespread in tomato fruitworm/corn earworm and beet armyworm, so other classes of insecticides should be used if management is needed.

Tomato fruitworm/corn earworm infesting a green tomato. Photo by Maria Cramer.

We continue to see high spider mites in many plantings. Spider mites tend to be worse in hot, dry conditions, and their populations can dramatically increase following broad-spectrum insecticides, which reduce their natural enemies. The first sign of their presence is often light-colored stippling seen on the top surface of tomato leaves. The mites causing this damage are usually found on the undersides of leaves, though with bad infestations mites will be found on the upper surface as well. When sampling spider mites, check 10 upper leaflets in at least 5 sites per field. The treatment threshold is 2 mites per leaflet on average (one of the individual leaves that makes up the compound tomato leaf). On farms where crop rotation is limited and the same miticides have been used for multiple years we’re seeing some miticide resistance — check whether and application has decreased mite populations, and if it did not work well, do not keep using it. Rotate between miticides and only treat when above threshold. Some products for spider mites in tomatoes include:

- Nealta (group 25)

- Oberon (group 23)

- Portal (group 21A)

- Agri-Mek (group 6) *7 day PHI

- Kanemite (group 20B)

- Acramite (group 20D) *3 day PHI

Spider mite stippling visible when looking at tomato leaves from above. The spider mites are generally found on the undersides of the leaves. Photo by Maria Cramer.

Peppers

In terms of most insect pests, peppers have been looking very good. We have seen aphids, spider mites, and thrips at low levels so far, however it’s important to keep in mind that thrips can transmit TSWV to peppers as well, and so monitoring and staying on top of thrips populations is crucial. As with tomatoes, finding and roguing out infected plants is important as well (see picture below for symptoms on foliage and fruit).

A) TSWV symptoms on pepper foliage — note mottling and cupping of the foliage. B) Symptoms on cherry pepper fruit. Photos by Maria Cramer.

As a reminder, we have found pepper weevils on pepper weevil traps in Gloucester, Cumberland, and Salem Counties this summer. Read more about pepper weevil biology and management here. If you think you may have pepper weevil on your farm or are interested in monitoring, please contact Maria Cramer.

Cole Crops

We are seeing many different kinds of caterpillars in fall cole crop plantings, including diamondback moth, imported cabbage worm, cabbage looper, cross-striped cabbageworm, and yellow striped armyworm. All cole crop seedlings can tolerate up to 10% infestation for these caterpillar. For heading cole crops between early vegetative and cupping, the treatment threshold is 30%. As heads form, the treatment threshold goes down to just 5% infestation. Sprayable Bt products (IRAC 11A) such as Dipel, Xentari, or Javelin can be effective on young imported cabbage worm, cross-striped cabbageworm, and yellow-striped armyworm caterpillars. Diamondback moth has resistance to many insecticide groups, and pyrethroids (IRAC 3A) and Bt products (IRAC 11A) are not effective for their management. Besides Bt, materials approved for caterpillar control include Entrust/Radiant (IRAC 5), Proclaim (IRAC 6), Torac (IRAC 21A), and Exirel (IRAC 28). For Bt products and contact insecticides, coverage on the undersides the leaves is essential.

Caterpillar pests of cole crops. A) Diamondback moth — smooth and tapered at each end. B) Imported cabbageworm — fuzzy and not tapered. C) Cabbage looper — characteristic looping behavior. D) Cross-striped cabbage worm — distinctive stripes, usually occurs in groups. Photos A-C by Maria Cramer, photo D from iNaturalist COO.

We saw downy mildew in cole crops this week. This is a disease that develops best around 50-59ºF and our cool night temperatures are making prime conditions for disease development. Downy mildew may appears as light-colored lesions on the top of the leaves and as masses of white spores on the lower surface. Scout at least 25 plants per field (5 plants in 5 locations), checking the undersides for spores. If you have downy mildew, rotate or tank-mix chlorothalonil 6F (FRAC M05) with another product listed in the Mid-Atlantic Veg Guide for downy mildew in cole crops, rotating MOAs. Use overhead irrigation at times of the day when leaves can dry quickly to slow disease progression.

Downy mildew spore masses on the underside of a collard leaf. Photo by Renee Carter.

Pumpkins and Other Cucurbits

Cucurbit downy mildew was first reported on 7/11/25 on cucumbers in central NJ and has been found on cucumbers and cantaloupe at the Snyder Research Farm in Pittstown. Growers should be applying protectants on cucumbers and cantaloupes for cucurbit downy mildew at this time. As of this post, we still haven’t found any instances of the disease on pumpkins, squash, or watermelon. For information on how to build an effective cucurbit down mildew control program, please reference this post by Dr. Andy Wyenandt and consult the Mid-Atlantic Production Guide for additional materials that can be used.

Cucurbit downy mildew symptoms on the upper surface (A) and underside (B) of cucumber leaves and symptoms on cantaloupe (C). Photos by Amanda Quadrel

In pumpkins, we continue to see squash bug eggs and nymphs. Consider treating for squash bug if you see more than one egg mass or group of nymphs per plant (see photos below). Aphid and mite populations are also increasing in many locations. Consult the Mid-Atlantic Production Guide for a list materials appropriate for aphids or mites.

Squash bug eggs (A), newly hatched nymphs (B), and an adult (C). Photos by Amanda Quadrel

We have also seen aphid populations building in some fields. While not causing direct damage to the fruits, the honeydew produced by aphids can stick to the fruits and attract hornets or promote sooty mold growth, resulting in unsightly fruit. If a colony is found at three or more sites in a ten site sample, growers may wish to apply control measures. There are several options available, such as Assail, Fulfill, PQZ, Sefina, and Beleaf that are labeled for aphids and are safer for bees. If also dealing with heavy mite populations, Minecto Pro can target both pests, but has a higher toxicity to bees.

Melon aphids infesting a pumpkin leaf. Photo by Amanda Quadrel.

Powdery mildew has shown up in most scouted sites. If more than one leaf in a 50 leaf sample is infected, fungicide programs for powdery mildew should be initiated.

Powdery mildew on pumpkin leaf. Photo by Amanda Quadrel.

We have also seen isolated cases of anthracnose, bacterial wilt, plectosporium, and phythophthora root rot. A preventative diseases management plan based on recommendations from the Mid-Atlantic Production Guide is important for suppressing many of these diseases. If you suspect diseases in your pumpkins (or other cucurbits), reference the “Diagnosing important diseases in Cucurbit crops” guide or send/bring samples to Rutger’s Plant Diagnostic Lab.

As always, please consult the Mid-Atlantic Commercial Vegetable Production Guide for a comprehensive list of materials that are labeled for specific crops and pests. As always, be sure to follow label rates and application instructions.

The Vegetable IPM Program wishes to thank the following Field Technicians, without whom much of the information presented weekly here would not be available. This week Nick Vergara of the Southern team went back to Rowan University for his fall semester — we appreciate all the work he put in this summer!

Southern team: Renee Carter and Kris Szymanski

Northern team: Martina Lavender, Coco Lin, and Cassandra Dougherty

Updates from EPA for Pesticide Users on How to Navigate Mitigation Measures to Protect Endangered Species

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced the availability of an online tool to help farmers and applicators implement mitigation measures to protect endangered species from pesticides. The mitigation measures were established to reduce exposure from pesticides for nontarget organisms as listed under the Endangered Species Act. Levels of mitigation that are required on pesticide labels can include mitigations for spray drift, runoff, and buffer zones. In April 2025, EPA released a mitigation menu website that includes information on these measures and how to calculate if a pesticide user has incorporated the number of “points” associated with the mitigation measures required by the pesticide labelling. It is the responsibility of the pesticide user to ensure that all pesticide labelling requirements are met, and requirements will vary among labels and products used.

The new tool released by EPA, the Pesticide App for Label Mitigations (PALM) is a mobile application that helps farmers and pesticide users use the EPA’s mitigation menu and stay compliant when applying pesticides for agricultural crop uses. The tool will combine relevant information and calculations needed to help farmers determine whether the necessary level of mitigation has been met before applying a pesticide.

If you are interested in learning more about the mitigation menu and available tools, the EPA will be hosting a public webinar on September 16th at 2 PM Eastern Time. Register here for the webinar.