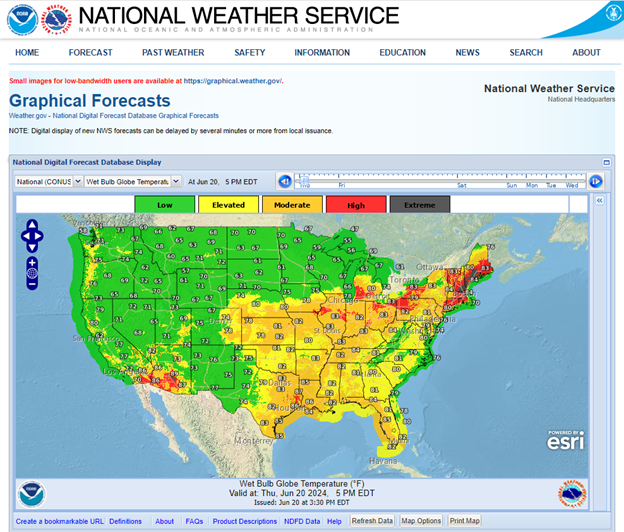

The National Weather Service has graphical forecasts for many weather variables including heat index and wet bulb globe temperature which can be used to evaluate risk of heat stress. These predictive tools may be utilized to evaluate the risk of heat stress up to one week in advance and may aid in planning of field activities.

The National Weather Service has graphical forecasts for many weather variables including heat index and wet bulb globe temperature which can be used to evaluate risk of heat stress. These predictive tools may be utilized to evaluate the risk of heat stress up to one week in advance and may aid in planning of field activities.

- Heat index: describes the apparent temperature based on air temperature and relative humidity in shady locations.

- Wet bulb globe temperature: incorporates air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed. May be more representative of field-based working conditions.

To access these graphical forecasts, visit https://digital.weather.gov/ and select either Wet Bulb Globe Temperature or HeatRisk experimental (i.e., heat index) from the drop-down menu. Zoom in to your location by holding your cursor over the area and scrolling with your mouse, or use the provided Zoom and movement tools in the upper left of the graph.

Article By: The Rutgers Farm Health and Safety Working Group: Kate Brown, Michelle Infante-Casella, Stephen Komar and William Bamka

Article By: The Rutgers Farm Health and Safety Working Group: Kate Brown, Michelle Infante-Casella, Stephen Komar and William Bamka

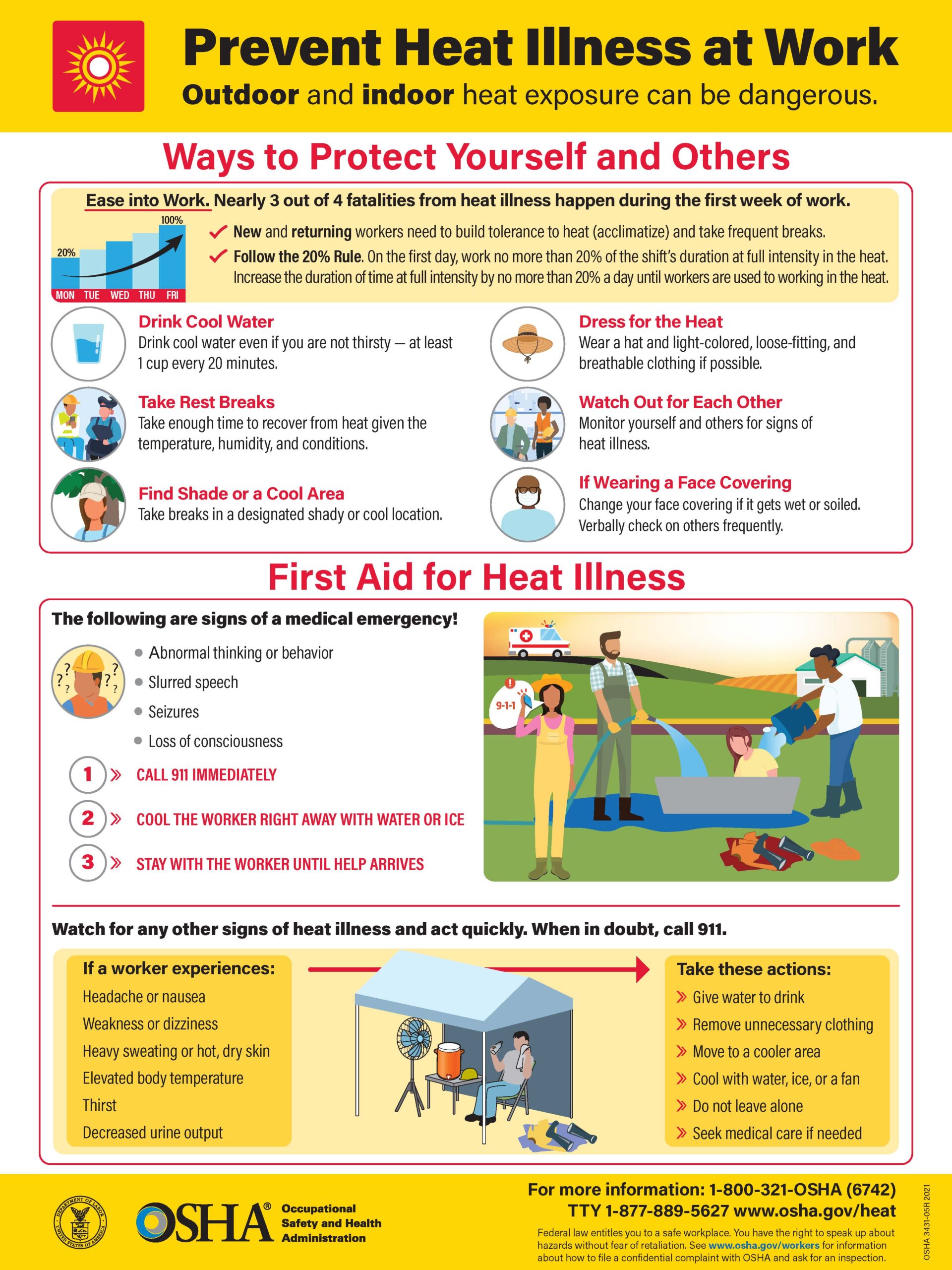

Article By: The Rutgers Farm Health and Safety Working Group: Kate Brown, Michelle Infante-Casella, Stephen Komar and William Bamka The outdoor nature of crop and livestock production exposes farmers and farm workers to variable weather conditions. During the summer months, periods of high heat can increase the risk of heat stress and heat-related illness.

The outdoor nature of crop and livestock production exposes farmers and farm workers to variable weather conditions. During the summer months, periods of high heat can increase the risk of heat stress and heat-related illness.