Thrips and tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) management were major challenges for multiple South Jersey growers in 2025, as well as in the previous few years. Several growers reported losing entire tomato plantings to the virus. Peppers were less impacted than tomatoes, but TSWV outbreaks did occasionally occur. As we move into pepper and tomato transplant production and the growing season for greenhouse tomatoes, having a multi-pronged approach for managing thrips and TSWV will give you the best chance of protecting your crop and avoiding losses. Below are key practices that can help keep thrips populations as low as possible:

Start clean. When transplants are infested with thrips prior to planting out, field infestations tend to occur early and be very difficult to control. To start clean:

- Never produce transplants in the same greenhouse with ornamentals. Ornamentals can harbor thrips and many are asymptomatic hosts for TSWV.

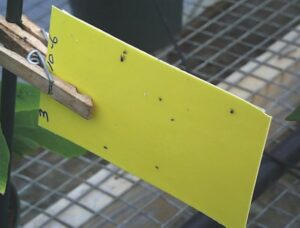

- Monitor thrips in planthouse with sticky cards and scouting (Fig. 1). There are no established thresholds for thrips in the greenhouse, but many growers use the first appearance of thrips as an action threshold.

- Keep greenhouses and high tunnels weed-free. Weeds can host both thrips and TSWV.

- If buying in transplants, segregate and monitor incoming transplants to ensure that they are not bringing in thrips.

- Treat transplants with imidacloprid (e.g. Admire) or Cyantriniliprole (Verimark) before setting in the field

Fig. 1. A sticky card being used to monitor greenhouse pests. Photo by S. Rettke.

Manage plantings to prevent the spread of thrips and TSWV from alternative hosts into tomato plantings. Thrips are attracted to pollen-producing plants, so populations can build up on plants that flower early, such as strawberries and small grains, then move into tomato plantings. Additionally, thrips can also overwinter on weeds. Using these facts, reduce the movement of thrips into tomato plantings by:

- Controlling weeds throughout the farm, especially in and around high tunnels

- Separating field plantings from greenhouses/tunnels, strawberry fields, and small grains

- Separating successive field plantings as much as possible. This way, if thrips and/or TSWV get out of control in one planting, they will not move directly into the next planting.

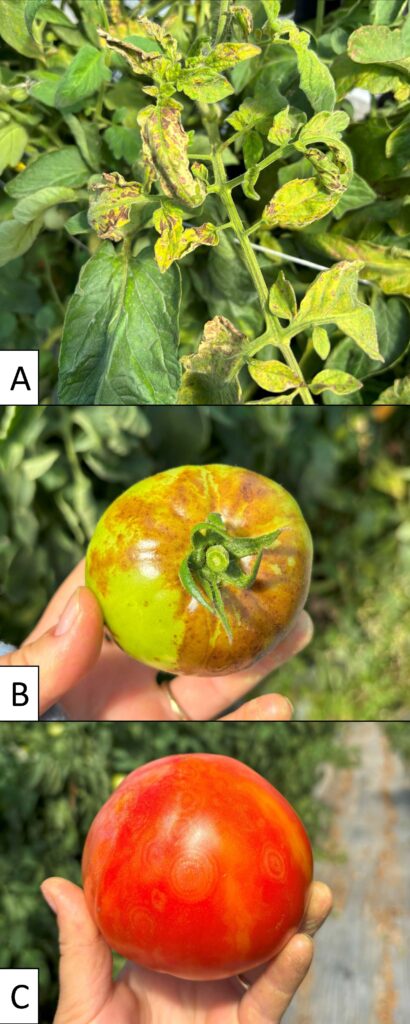

- Scouting for tomato spotted wilt virus symptoms (Fig. 2). Immediately rogue symptomatic plants to avoid secondary spread within the field.

Fig. 2. TSWV symptoms in tomato: a) curling and yellowing foliage symptoms, b) distortion and brown shoulder symptoms on green fruit, and c) bulls-eye symptoms on ripe fruit. Photos by M. Cramer.

Use metallized plastic and resistant varieties.

- Use metallized plastic mulch when possible (Fig. 3). Metallized mulches reflect sunlight, disrupting thrips navigation and making it harder for them to colonize plants. These plastics are widely used in states like Florida that have historically had serious thrips problems. Because these mulches reflect solar radiation, they lower bed temperatures, and will slow down tomato growth early in the season. This should be taken into account when planning to use them.

- Use TSWV resistant tomato and pepper varieties. While some farms have reported resistance-breaking TSWV, others continue to report that resistance is still holding up.

Fig. 3. Metallized plastic laid in the fall to control onion thrips in alliums. Photo by A. Quadrel.

Use best practices around insecticides. Thrips are difficult to manage with insecticides because they tend to hide in hard to reach parts of the plant or in the soil as well as their rapid ability to develop resistance. For example, many thrips populations in south Jersey are resistant to Radiant (IRAC 5), making this insecticide ineffective for management. Pyrethroid (IRAC 3) resistance is also widespread. Many of the insecticides labeled for thrips are only partly effective, and none are able to “knock down” high populations. To get the best efficacy out of insecticides:

- Know what your populations are: Monitor thrips populations and treat when populations start building, but are still low.

- Scout 5- 10 locations in field at least once a week

- At each location in the field, pick a group of 5 consecutive plants and check 2 leaves on each plant (10 leaves total per location)

- Count the number of thrips on the leaves (Fig. 4). Research from North Carolina shows that the species of thrips vectoring TSWV (western flower thrips) are most reliably found on the leaves rather than the flowers

- Threshold: Action should be taken if counts are increasing towards ~ 5 thrips per 10 leaves on average

- Rotate modes of action as much as possible. We believe that thrips populations tend to be highly localized, and thus you are managing insecticide resistance for your population of thrips specifically. The more you manage resistance, the more product options you will continue to have.

- Monitor thrips populations after treatment to assess efficacy (some systemic products, such as Beleaf and Verimark may take several days to ~a week to impact thrips populations)

Note: The vegetable IPM program offers scouting services throughout New Jersey if you are unable to scout your plantings (you can find a description of services here). We also offer training for scouts employed by growers. Finally, private companies can also provide scouting services.

Fig. 4. Five thrips on a tomato leaf.

Plan what products you will use and when. The following table lists conventional products that can be used for tomato pest management. Choose products from a variety of IRAC groups to prevent resistance development and prolong efficacy.

| IRAC group | Product name | Ai | Efficacy

* = suppression only |

Notes on use |

| 1A | Lannate | Methomyl | Good | New EPA restrictions on annual applications (<13 lbs AI/acre/year) and mitigations for runoff and drift. Not labeled specifically for thrips in tomatoes, but can be used |

| 1B | Dimethoate | Dimethoate | Good | Not labeled specifically for thrips in tomatoes, but can be used |

| 4A | Admire | Imidacloprid | Good | Only labeled for tobacco thrips. For treating transplants before transplanting |

| 5 | Radiant/

Entrust |

Spinetoram/

Spinosad |

Excellent, except where resistant | No more than 3 applications in a season. Widespread resistance issues in South Jersey |

| 13 | Pylon | Chlorfenapyr | Excellent | Only for greenhouse tomato production– i.e., not for transplants or field production. Not to be used on tomatoes that are <1” diameter at harvest. |

| 15 | Rimon

|

Novaluron | Good* | Foliar. No more than 2 applications against thrips in a year. Can be used in greenhouses and high tunnels. Larvae only |

| 21A | Torac | Tolfenpyrad | Fair | Foliar. No more than 2 applications in a season |

| 23 | Movento | Spirotetramat | ? | Foliar. No more than 2 applications in a season (at 5 fl oz/A thrips rate). Larvae only |

| 28 | Harvanta | Cyclaniliprole | Fair* | Limit of 3 applications per season (at 16.4 fl oz/A thrips rate) |

| 28 | Verimark | Cyantraniliprole | Fair* | Tray drench just prior to planting or drip irrigation. No more than 2 applications per year. Limits when ai is being used foliarly (e.g. Exirel) as well |

| 28 | Exirel | Cyantraniliprole | Fair* | Foliar. Recommend early in the season for new transplants. Limitations on ai use |

| 29 | Beleaf | Flonicamid | Excellent | Only labeled for thrips when used through drip. No more than 2 applications per year |

| 30 | Incipio | Isocycloseram | Excellent | New for 2026. No more than 2 applications per year |

When using pesticides, the label is the law. Always make sure the product you use is registered in your state and for your crop(s). Follow all application restrictions.

Biological insecticides. There are many biological products that are labeled for tomatoes in the greenhouse, tunnel, and field. While we do not have efficacy information for these, some growers have reported good results in tunnels and greenhouses with Grandevo WDG (Chromobacterium subtsugae and spent fermentation media), LALGUARD M52 OD (active Metarhizium brunneum), and Bronte (inactivated Burkholderia rinojensis cells and spent fermentation media). Biological insecticides may have specific storage and handling instructions in order to achieve maximum efficacy.

In conclusion, use a multi-strategy approach for thrips and TSWV management. In particular, use resistant varieties and preventative practices to reduce thrips populations and TSWV spread on your farm. When using insecticides, time applications based on action thresholds, monitor efficacy, and rotate IRAC groups in order to prevent the development of insecticide resistance.

By: Maria Cramer, Amanda Quadrel, and Andy Wyenandt.

Articles in this section contain information helpful to the NJ commercial organic grower.

Articles in this section contain information helpful to the NJ commercial organic grower.