- Cucurbit downy mildew has been confirmed on cucumber in New Jersey. To date, cucurbit downy mildew has been reported on cucumber and melon in the mid-Atlantic region. All cucumber growers need to add a downy mildew-specific fungicide to their weekly fungicide programs. All cucurbit growers need to scout on a regular basis.

- There have been no new reports of Late blight in tomato or potato.

- Dickeya dianthicola has been confirmed in 12 states to date. All potato growers are encouraged to scout fields and report any suspect plants/tubers. The best method for keeping your potato operation Dickeya-free is to adopt your own 0% Dickeya-tolerance policy. Click here for the latest Dickeya update.

- Pepper anthracnose is being reported in southern New Jersey.

- Cucurbit powdery mildew is active on all cucurbit crops.

Archives for August 2016

Vegetable Disease Briefs – 8/15/16

More Backyard Poultry

It was pointed out to me in my previous backyard poultry post that Rutgers has few resources about backyard poultry and many of these are older. I put together a set of resources that can be used as an overview about small flocks and backyard poultry. Most of these are taken from the University of Kentucky, which has an excellent set of backyard poultry materials (Kentucky Extension Services).

- Backyard Egg Production

- Feeding Chickens

- Evaluating Egg Laying Hens

- Egg Production

- Small Flock Problems

- Processing Chickens

- Chicken Breeds

- Chicken Breeds (Pictures)

- Duck Breeds

- Geese Breeds

- Turkey Breeds

- Raising Guinea Fowl

- Hoop Housing for Poultry

- Reading a Feed Tag

- External Parasites of Poultry

Michael Westendorf e-mail: michael.westendorf@rutgers.edu

Potato | Tomato Disease Forecast 8-12-16

Click to View | Download Report 8-12-16

Potato Disease Forecasting Report

We will be tracking DSVs for Late blight development and calculating P-days for initiating the first early blight fungicide application.

The first late blight fungicide application is recommended once 18 DSVs accumulate from green row. Green row typically occurs around the first week in May in southern NJ. An early season application of a protectant fungicide such as mancozeb (Dithane, Manzate, Penncozeb) or Bravo (chlorothalonil) as soon as the field is accessible is suggested. Please be vigilant and keep a lookout for suspect late blight infections on young plants. No late blight has been reported in our region to date.

Remember the threshold for P-days is 300! Once 300 P-days is reached for your location, early blight fungicide applications should be initiated. Growers who are interested in using this model should choose the location above that is closest in proximity to their farming operation and should regularly check the Cornell NEWA website (http://newa.cornell.edu/) where this information is compiled from. Click on Pests Forecasts from the menu, select your weather station, and click on tomato diseases, set accumulation start date, and a table of daily and total DSVs will be generated.

Disease severity values (DSVs) for early blight, septoria leaf spot, and tomato anthracnose development are determined daily based on leaf wetness (due to rainfall, dew) and air temperature.

On a daily basis DSV values can range from 0 to 4 where 0 = no chance for disease development to 4 = high chance for disease development.

DSVs are accumulated during the production season.Fungicide applications are based on an individually determined DSV threshold. The first fungicide application for the control of these three diseases is not warranted until 35 DSVs have accumulated from your transplanting date. After that, growers can base fungicide applications on different DSV thresholds.

Reports generated by Ryan Tirrell

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Veg IPM Update: Week Ending 8/10/16

Sweet Corn

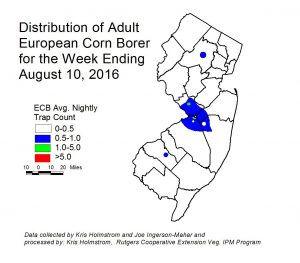

European corn borer (ECB) adult activity continues to be very low. Areas of highest activity have shifted to the central counties, and particularly Mercer County (see ECB map). As always, consider treating when the number of infested plants in a 50 plant sample exceeds 12%. Any planting remaining at or above threshold as it proceeds to full tassel should be treated, as this is the last stage at which ECB larvae will be exposed and vulnerable to insecticidal sprays. See the 2016 Commercial Vegetable Recommendations Guide for insecticide choices.

European corn borer (ECB) adult activity continues to be very low. Areas of highest activity have shifted to the central counties, and particularly Mercer County (see ECB map). As always, consider treating when the number of infested plants in a 50 plant sample exceeds 12%. Any planting remaining at or above threshold as it proceeds to full tassel should be treated, as this is the last stage at which ECB larvae will be exposed and vulnerable to insecticidal sprays. See the 2016 Commercial Vegetable Recommendations Guide for insecticide choices.

Backyard Poultry

Backyard poultry phenomenon requires vet retraining

Taken from Feedstuffs Magazine (Online Journal) August 10, 2016 (Feedstuffs Online Magazine)

Backyard poultry is becoming more and more commonplace for a variety of reasons, such as local food webs or the desire for non-traditional pets. These chickens are also coming into the neighborhood animal clinic for veterinary care.

“These backyard chickens are not just providing fresh eggs; they are pets, and when ‘Henny Penny’ is sick, she needs to see the doctor,” said Dr. Cheryl Greenacre, a professor at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.

Greenacre, who specializes in avian medicine, presented at the American Veterinary Medical Assn. (AVMA) Convention held Aug. 5-9 in San Antonio, Texas.

While backyard poultry is a growing phenomenon, the numbers are more than a bit elusive. In a 2010 study, the National Animal Health Monitoring System, an arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, surveyed metro areas of Miami, Fla.; Denver, Colo.; Los Angeles, Cal., and New York City to gather urban coop statistics. Approximately 0.8% owned chickens, but nearly 4% more planned to have them within five years, Greenacre noted.

Information gathering remains an ongoing priority for some university extension services, but it is clear that those numbers are affecting the local veterinarian’s practice. Small-animal practitioners may not be trained in avian medicine, while others often do see pet birds in their practice.

“One of the most common reasons why veterinarians see chickens is an attack by a predator,” Greenacre said. “However, when it comes to treatment, the biggest and most important difference is that backyard poultry are food animals. They provide eggs, and sometimes meat, for human consumption, so the medicines these birds can receive are under a different set of rules. We need to provide education for our veterinarians to meet the demand of this up-and-coming market segment.”

In addition to gaining the knowledge needed through conferences and other continuing education opportunities, veterinarians can tap into certain websites for vital information, like the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Databank, the go-to source for drug use in chickens.

It is imperative that veterinarians treating poultry become educated on proper medication use in a food animal, according to Greenacre, because certain drugs are prohibited by the Food & Drug Administration, others are considered off label and still others are approved for use only in specific instances and under certain conditions, such as age, concentration, duration or frequency.

Backyard poultry enthusiasts themselves have to sift through the mountains of material available to obtain correct information about their flocks. Some information flies in the face of animal welfare, she said, and condones harmful at-home treatments for certain conditions, such as bumblefoot, an infection on the bottom of a chicken’s foot.

“From books to the internet to radio shows and magazines, there is a variety of advice out there regarding backyard poultry,” Greenacre said. “The best sources are university extension services and your veterinarian.”

However, with these pets come cautions unfamiliar to owners of dogs and cats. “Veterinarians should educate owners on the risk of salmonellosis in humans from handling poultry,” Greenacre emphasized. “Elderly people, children less than five years old and any immunosuppressed individuals are most at risk for a fatal infection. Careful hand washing is a must after any contact with the poultry.”

Owners of backyard poultry also have to be aware of biosecurity measures and be able to recognize and prevent spread of disease, especially avian influenza and exotic Newcastle disease. Anyone experiencing sudden deaths or high mortality should contact their veterinarian immediately. Other actionable measures are to quarantine new birds, to not share tools or egg cartons and to always clean and disinfect the coop.

“Veterinarians need to hone their expertise in this area and team up with backyard poultry owners,” Greenacre said. “Together, we can provide the best care possible and keep these flocks healthy.”

Michael Westendorf e-mail: michael.westendorf@rutgers.edu

Dickeya dianthicola update: 8/10/16

In addition to Dickeya dianthicola being found in potato fields in New Jersey, the pathogen has also been detected in fields from Long Island to Florida this summer. To date using PCR test results and North American Certified Seed Potato Health Certificates to track Lot No., the pathogen has been detected in 12 states (DE, FL, MD, MA, NJ, NY, NC, PA, RI, VA, WV, and OH). Potato growers, crop consultants, and Extension personnel in states which grow potatoes from Maine or New Brunswick, Canada should remain vigilant by scouting their fields for Dickeya symptoms on a regular basis and by submitting any suspect samples for diagnostic testing. Dickeya dianthicola has been detected in the US in the past, and because of this, APHIS just recently announced that the pathogen has been designated as a non-reportable/non-actionable pathogen despite its potential to cause 100% crop loss. A link to the USDA/APHIS website for information on Dickeya dianthicola detection and control can be found here.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misrepresentation of Dickeya dianthicola being presented to potato growers in the region.

- Dickeya is not a significant problem. To date its has been detected in seed in 12 states originating from 2 sources and a number of suppliers. In Maine, when dormant tuber testing was done for lots from 2015, there was approximately 16% incidence of Dickeya in 347 samples tested. In the dormant tuber testing for 2016, 25% tested positive for Dickeya out of 350 samples. Importantly, there is no current policy in place designed specifically for regulating and/or controlling Dickeya dianthicola in potato in Maine. There is also no way of knowing which of the above said lots (varieties) tested positive for Dickeya.

- Dickeya is Blackleg. Dickeya is Dickeya, not Blackleg. Dickeya is seed-borne. Blackleg is mostly soil-borne. Blackleg is caused by other ‘pecto’ or soft rot bacteria. Blackleg can be found in almost any potato field that has been in potato production in the past. Dickeya has only be found in fields planted with infested seed over the past few years.

- Dickeya is endemic. If so, why wasn’t it reported as causing significant problems in potato prior to 2015/2016. Even without proper testing available, it would have would been noticed by potato growers to cause concern/raise alarms.

- Dickeya is the result of the current environment. What has changed between now and prior to its first detection in the US in 2014?

- The disease is less severe 2016 than in 2015. Dickeya is being tested for and reported more often in 2016 now that it has been brought to the attention of potato growers. Growers who received infested seed are reporting variable losses to Dickeya in 2016. Growers who have planted back into infested fields are also reporting poor plant vigor and variable yield losses.

- Varieties differ in susceptibility to Dickeya. Dickeya has been detected in different lots of the same variety from different suppliers in 2016. Dickeya has also been confirmed in different varieties from the same supplier in 2016. Symptoms of Dickeya may appear different between cultivars.

The best method for keeping your potato operation Dickeya-free is to adopt your own 0% Dickeya-tolerance policy.

For more information on Dickeya please see the following articles posted online – source(s) of information:

Dickeya: A new potato disease – Growing Produce

Blackleg is Once Again Being Observed in Potato Fields Across the Mid-Atlantic Region – Penn State University

Update on Dickeya detections in potato – University of Delaware

Dickeya Blackleg: New potato disease causing major impact. – Cornell University

Watch for Dickeya – a new potato disease – The Ohio State University

High security Aroostook farm advances tater technology. – Maine Potato Board

Slowing Dickeya, other pathogens in Canada. – North Dakota State University

Dickeya: A new threat to potato production in North America. – SPUDsmart

Dickeya is coming. – University of Wisconsin/North Dakota State University

Maine ‘Ground Zero’ for new potato disease. – Maine Department of Ag.

Maine seed potato growers looking to protect brand against disease. Maine Department of Ag./Maine Potato Board