Cranberry toad bugs (Figure 1) should be the last insect pest of concern this season. Growers should start monitoring for this insect from now until the end of July.

Figure 1. Toad bug nymph. Photo by Elvira de Lange

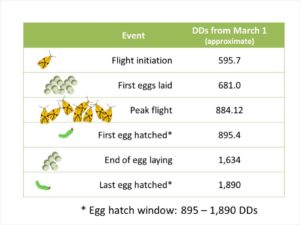

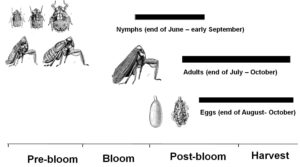

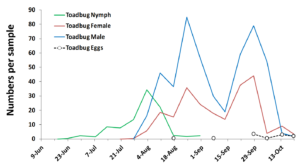

Life cycle. Toad bugs, Phylloscelis rubra (Hemiptera, Dictyopharidae), feed only on cranberries. This insect has a single generation per year. It overwinters as eggs. The nymphs appear by the end of June through early September; nymphal abundance peaks between last week in July and 1st week in August (Figure 2). The adults emerge from end of July through October (harvest) and eggs are laid from end of August through October (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows seasonal abundance of toad bug nymphs and adults in New Jersey cranberries based on sweep net samples.

Figure 2. Toad bug life cycle

Injury. Feeding injury can be noticed in two stages. First stage feeding injury on vines causes closing in (towards the branch) of the leaves on the new growth. Second stage feeding causes changed in color (reddish to brown) of new growth (Figure 4). The injury can be seen from July until harvest. This injury will cause dying of the branch and the berries to shrivel up (Figure 4). Heavy infestation will result in dwarfed berries.

Figure 3. Seasonal abundance of toad bugs in cranberry bogs

Figure 4. Toad bug injury to cranberries

Management. To determine infestation levels, lightly sweep problematic beds (bugs should be easy to catch in sweep nets as they are very active). There is currently no threshold established. Thus, insecticide applications should be based on the relative number of bugs per sweep compared with other sites and previous history of infestation. Currently, growers can use the following control options: Sevin 4F (carbamate), Diazinon, Imidan 70W (organophosphates), Actara or Assail 30SG (neonicotinoids). If infestation is high, treatments should be applied before the 1st week of August.