Doppler radar polarimetric technology from iWeatherNet.com: Rainfall totals for the last 24 hours to 3 days – high resolution map shows a widespread system brought much needed precipitation to South-Central NJ Sunday, July 31st though the 72-hour period ending August 2, 2022. In Salem County, areas along the Delaware River to west of Woodstown received 5/10ths to 9/10ths in parts of Mullica Hill. A wider swath through Woodstown and Glassboro provided 3/10ths to less than an inch. A narrower swath of 7/10ths to one inch fell from Elmer to Williamstown. Localized areas west of Salem City and South of Abbottstown Meadow received an inch of accumulation. Less than 3.0 inches of rain have been recorded below Memorial Lake at the USGS 393838075194901 Woodstown USGS Gauge for the month of July.

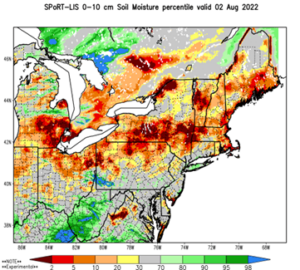

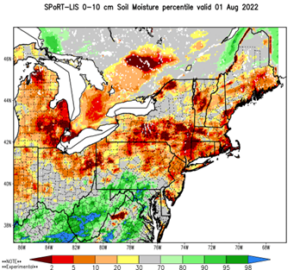

Looking at the Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center map , soil moisture for surface to ten cm depth readings shifted from below the 3-percentile category for much of the county on August 1st to the 30th percentile as of August 2, but a large area of production remains in the five to ten percentile.

, soil moisture for surface to ten cm depth readings shifted from below the 3-percentile category for much of the county on August 1st to the 30th percentile as of August 2, but a large area of production remains in the five to ten percentile.

The July 1, 2022, beef cow inventory compiled by USDA NASS

The July 1, 2022, beef cow inventory compiled by USDA NASS