Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Monmouth, Cumberland, and Middlesex County have developed a brief needs assessment survey to gain a better understanding of the educational materials and technical resources that are needed in the nursery and landscape industries to help promote the production and marketability of native plants.

If you operate a nursery, greenhouse, or landscape business in NJ and grow native plants (or have an interest in starting to grow native plants), please fill out this 5-minute online survey to help Rutgers Cooperative Extension develop resources and programs to support our green industries.

Survey Link: https://go.rutgers.edu/ojkdrelv

Or scan the QR code below to access the survey:

For more information contact Bill Errickson, Agriculture Agent RCE of Monmouth County: william.errickson@njaes.rutgers.edu 732-431-7260

Printable Flyer: RCE Native Plant Survey Flyer

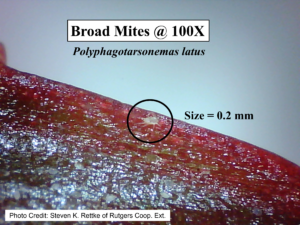

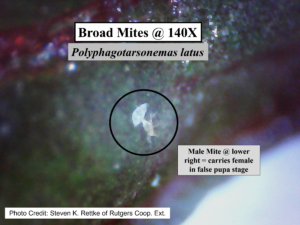

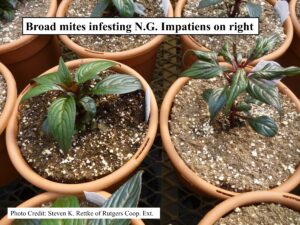

Dealing with Broad Mite, Greenhouse Product News

Dealing with Broad Mite, Greenhouse Product News