This Rutgers Plant & Pest Advisory blog will review a few of the landscape summer pests specific to mostly oak trees (Quercus). The scarlet oak sawfly will be discussed first, followed by the oak spider mite & finally the oak lace bug. All three pest species have multiple generations during the summer months & therefore can be observed throughout most of the season. None of the pest species are usually considered to be life-threatening to oak hosts but they can cause significant & undesirable aesthetic injuries. However, it could be stated that these pests may have bark, but they have little bite. Therefore, with large oak trees the spraying of many gallons of pesticides would not be justified.

Mimosa Webworm Activity Begins

Mimosa webworm early webbing of honeylocust leaflets at outer branches. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Mimosa Webworm (Homadaula anisocentra) = (880-1200 GDD = 1st generation egg hatch): The overwintering pupal cocoons of this non-native caterpillar emerged as adults last June & eggs have been laid on leaflets or small twigs of honeylocust (Gleditisia tricanthos ) trees in NJ. This caterpillar also feeds on mimosa trees, but since honeylocust plantings in the urban environment are more common, we usually encountered them on these trees. Within many areas of the state, the early, initial 1st generation webbings by 1st instar caterpillars are now becoming noticeable at the outer edges of the leaf canopy.

Some Key Soft Scale Pests in the Landscape

Soft Scale Species Controls (June & July): Compared to armored scales, the soft scales are relatively easy to suppress with either contact sprays or systemic treatments. Some of the common landscape soft scale species in NJ include calico, Fletcher, Indian wax, cottony maple, cottony camellia, spruce bud, European fruit lecanium, pine tortoise, striped pine, magnolia, & tulip tree. Although large soft scale adult females are more difficult to control, the immature nymphs are often vulnerable to sprays when good coverage is achieved. However, there are some species that have proven to be more challenging to control. Two good examples include the calico scale & Indian wax scale species. Horticultural oil sprays are often recommended to control immature scale nymphs, but sometimes against the calico & Indian wax species the efficacies are less consistent. This blog will first review soft scale management options & then show photographs & discuss the life cycles of the following soft scale species with crawlers emerging during June & July: (1) Indian wax, (2) calico, (3) cottony camellia, (4) spruce bud, & (5) Fletcher.

COVID Delta Variant and NJ Agriculture

As the farming season progresses so does concern for the increased prevalence of the COVID Delta variant in the region. We asked Don Schaffner, Extension Specialist, about the Delta variant and if we should be concerned about it. If you or your farm workers are in need of a vaccine please email njfarmvax@njaes.rutgers.edu and an Extension team member will assist you with finding local vaccination locations and/or determine if an on-farm vaccine clinic is possible for your workers. If you have questions about the vaccine visit the Rutgers On-Farm Food Safety Vaccine Education for Growers website for information in multiple languages.

Meredith Melendez: Are we seeing an increase in cases of the COVID Delta variant in New Jersey or the region?

Don Schaffner: Yes. According to CDC, Region 2 (New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands) had only 3.1% of all infections due to the Delta variant for the week ending 5/22/21. This percentage had jumped to 17.7% week for the week ending 6/5/21. There are not further updates at this time.

Also according to the CDC in NJ 3.4% all infections were due to the Delta variant for the week ending 5/22/21. No further New Jersey specific updates are available at this time.

MM: How is the Delta variant different than the COVID cases we saw over the past year?

DS: There are a number of reasons why there is increased concern over the Delta variant. Epidemiological data shows that the variant has increased transmissibility (i.e. it is more easily spread from person to person) than the original strain. Estimates indicate that it is about 60% more transmissible. This means that for every one person infected by the original virus, on average for the same conditions the Delta variant would spread to about 1.6 people.

One of the ways of combating the virus once someone is infected is with monoclonal antibody treatments. There is evidence that the Delta variant is more resistant to this important treatment.

There is also evidence that the Delta virus is not as readily neutralized by post-vaccination sera. Sera contain the antibodies in people that are vaccinated.

MM: Are the Pfizer, Moderna, and J&J vaccines as effective against the Delta variant?

DS: Yes. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine appears to be about 60% effective against the delta variant. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are about 88% effective after the second dose (vs. over 90% for other variants). So while the vaccines are less effective against the Delta variant, it is still much better to be vaccinated than not.

MM: Why should someone get vaccinated now if they haven’t already?

DS: Unvaccinated individuals are vulnerable to all variants of the virus. These variants arise through the natural evolution when the virus replicates inside a sick person. Since the vaccines can stop some people from getting infected, the more people that are vaccinated the better control we will have over these variants and stop new variants from evolving.

Some Key Armored Scales & Crawler Emergence

A Large-Scale Dilemma:

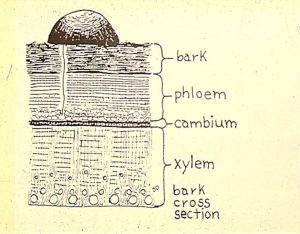

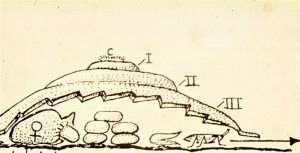

Drawing shows a shrinking female armored scale laying eggs. Waxy covers of each of the 3-instars are pushed above the other. Crawlers emerge from the female cover through the one-way flap. (Drawing Credit: John Davidson, Univ. of MD)

Undoubtedly many arborists, landscapers, nurserymen, and golf course superintendents would agree that effectively controlling scale insects is one of the more frustrating pest management challenges encountered. Of the half-dozen major families of scale insects common in the urban landscape, the armored scales are the most troublesome. With their protective waxy covering, armored scales are considerably less susceptible to various insecticide spray treatments.

Reddish colored crawlers of Pine Needle Scales emerging out from under female waxy covers. (Photo Credit: Ohio State Coop. Ext.)

Historically, many pesticide spray applicators fail to achieve satisfactory controls because they do not have the time or inclination to apply sprays during the scale crawler emergence periods. To complicate matters, the crawler periods for the various armored scale species are quite variable. Furthermore, the improper timing of long residual pyrethroid insecticides can virtually eliminate important parasitoid bio-control activity and hence, often encourage scale infestations. The intention of this blog is to stress the importance of properly timed treatments to achieve better management of scale insects. This is especially true when attempting to control armored scales.

Despite the complications stated above, fortunately some relatively newer insecticides have given improved abilities for scale controls. These newer materials & the life cycles of 5-armored scale species will be covered in this blog. The scales covered include: 1-Euonymus scale; 2-Cryptomeria scale; 3-Japanese maple scale; 4-White Prunicola scale; & 5-Juniper scale.

Landscape Pest Notes: Some Late-Spring Insects (Part 2)

Since there are still over 4-weeks before the official start of summer, the accumulation of growing-degree-days (GDD) will continue to accelerate over the next several weeks. Many of our landscape insect pests will be rapidly emerging and be entering their best control windows before they potentially cause feeding symptoms. This writing contains part 2 of 2 parts of only a handful of the many late spring landscape insect pests that require monitoring. Some could more properly be called mid-spring pests, especially in southern NJ. Those included within part 2 of this blog are: Taxus mealybug; Boxwood leaf miner; Aphid species and Bronze birch borer.