This Rutgers Plant & Pest Advisory blog will review a few of the landscape summer pests specific to mostly oak trees (Quercus). The scarlet oak sawfly will be discussed first, followed by the oak spider mite & finally the oak lace bug. All three pest species have multiple generations during the summer months & therefore can be observed throughout most of the season. None of the pest species are usually considered to be life-threatening to oak hosts but they can cause significant & undesirable aesthetic injuries. However, it could be stated that these pests may have bark, but they have little bite. Therefore, with large oak trees the spraying of many gallons of pesticides would not be justified.

Spraying many gallons of a pesticide against most pests on a large oak as shown above is rarely justified. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Scarlet Oak Sawflies (Caliroa quercuscoccineae): Another common name sometimes used for this insect is the oak slug sawfly because they appear slug-like. The growing degree range for this species does not appear to be well established, but if 3-generations occur, then they can be active for 3-months from early June through early September within NJ. The scarlet oak sawfly is primarily considered to be a native forest insect & will likely be only observed in residential or commercial landscapes located adjacent to extensive wooded areas. Therefore, they will probably not often be encountered within more urban settings.

Scarlet oak sawfly larvae feeding symptoms. The lower leaf epidermis layer & interior cells have been removed. Only the upper epidermis layer remains. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Despite the common name, the scarlet oak sawfly can be found feeding on numerous oak tree species, such as the red, pin, black, scarlet & also trees within the white oak group. The slug-like appearance of the larval stages of this sawfly are distinctive. Their elongated, unsegmented bodies are covered with a slimy, mucoid material that are composed of their own excrement. Since they lack any pronounced prolegs, the slimy coating allows them to better adhere to leaf surfaces. In addition, this coating may deter attack by predators.

The slug-like larvae have a mucoid covering that allow the sawflies to adhere to leaves. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Scarlet oak sawflies have a unique feeding behavior by the younger instar larvae. As the photograph taken by Joe Boggs (Ohio State Coop. Ext.) illustrates, the early larvae feed closely together, side-by-side as they move across the bottom surfaces of oak leaves. Only the leaf veins & upper leaf epidermis are left in place & not consumed. The initial leaf symptoms after this feeding produces a windowpane appearance, as another photograph shows the translucence. As the larvae begin to reach maturity, the previous organized feeding is discontinued as they more randomly & independently move across the leaves. Eventually, the windowpane leaf symptoms change as the upper epidermis dries & begins to fall-out & produce skeletonized symptoms with large open holes between the veins.

As the sawfly larvae reach maturity, they will feed & move in a more random or independent pattern. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Early nymphal instars of oak sawfly move together in a single file pattern. As they feed, they scrap away the lower leaf epidermis. (Photo Credit: Joe Boggs, Ohio State Coop. Ext.)

At the end of each generation, the mature sawfly larvae will drop from the tree to complete development & pupate inside cocoons within the leaf litter. After the black-colored adult sawflies emerge & mate, the females will then use their ovipositors to insert eggs along major oak leaf veins.

Although it has already been stated that infestations from this sawfly are generally not life-threatening to oak hosts, alternatively, it can be stated that the scarlet oak sawfly can potentially defoliate oak trees repeatedly over a few consecutive years. If this occurs, the trees can be stressed enough where they can become susceptible to wood borers, such as the two-lined chestnut borer. This same scenario occurs with gypsy moths when they defoliate oaks over a few consecutive years. Wood borers are the “true assassins” of our woody ornamentals.

The translucent feeding symptoms by the oak sawflies has destroyed the photosynthetic abilities of this leaf. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

If populations occur on smaller oak trees, then lesser infestations can be physically removed & destroyed. Larger infestations of young larvae can be successfully suppressed with horticultural oil sprays. Mature larvae can be controlled with an assortment of contact insecticides. Spinosad (Conserve) is a reduced-risk material & is labeled against these sawfly larvae. (Reference: Ohio State Coop. Ext., On-Line Fact Sheet by Joe Boggs)

Oak Spider Mites (Oligonychus bicolor)(802-1265 GDD = 1st generation emergence): These spider mites begin to be observed after the overwintering eggs hatch in late June in NJ. Feeding symptoms can continue throughout the summer months as multiple generations lay additional eggs. The oak spider mite is classified as a warm season mite species. Like all spider mites, they thrive in dry conditions. However, what is unique with this species within the Oligonychus genus is the fact that they feed on the upper surface of leaves. Although infestations are highest on the foliage of lower branches, they still lack the protection from dust, UV light, & rain that would be found on the undersides of the leaves. The odd behavior would seem to cause an evolutionary disadvantage & produce smaller populations, but their numbers can still build-up to reach high levels.

Various signs from oak spider mites are observed on the upper leaf surface of the sawtooth oak leaf. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Turn the sawtooth oak leaf over to view the undersides & it appears clean. No spider mite signs observable. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

With their piecing-sucking mouthparts, they feed in leaf plant cells & remove fluid contents. The resulting death of cells causes a fine chlorotic stippling that is initially dull & yellow. As the dead tissues dry, the bronzing symptoms appear on upper leaf surfaces. This species primarily feeds on red oak group oaks, especially pin oaks (Quercus palustris). However, they potentially can also be found feeding on chestnut, elm, beech & maple trees. Trees growing around impervious surfaces such as along streets or within parking lots will often have higher infestations because of the elevated temperatures at these locations.

Feeding symptoms by oak spider mites can be seen on these oak leaves. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

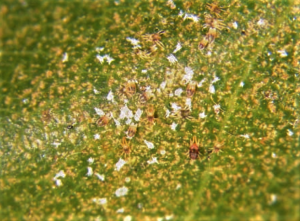

Oak spider mite feeding symptoms & signs will often be seen concentrated along major leaf veins. The white eggshells & white cast skins can usually be easily observed located within the crevices of the veins. Eggs laid on upper leaf surfaces will mature to become reddish & barrel-shaped before hatching. Since this mite species overwinters as eggs, the final generations of the season will begin laying their eggs on woody bark. Usually, most of the eggs will overwinter on the tree trunk & major branches. With heavy infestations, a thick webbing resembling rusty, fiberglass insulation will cover the overwintering eggs. Sometimes a continuous, long-extending webbing can be seen occurring along the woody bark.

Closer view allows the white cast skins & white egg shells to be seen congregating along the crevices of the leaf veins. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

An even closer view shows a greater accumulation of spider mite cast skins & egg shells as the color contrast makes these signs obvious. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

If infested trees are small, then oak spider mites can potentially be successfully managed by thoroughly spraying foliage with a strong, jet-spray of water. Properly targeted sprays can knock-off the adults, immatures, & eggs from the leaves. It will be difficult for them to climb back up the tree. This will probably have to be followed-up with several additional water sprays during the summer. Also, be certain not to apply excessive levels of nitrogen. This will encourage higher spider mite reproduction levels.

Active oak spider mites & eggs can be washed off leaves with a strong jet-spray of water. (Photo Credit: David Shetlar, Ohio State Coop. Ext.)

With larger trees, other control strategies will be required. When dealing with trees in the landscape, miticides are not recommended unless stippling damage is evident on more than 10% of the foliage & beating tray counts average more than 10 mites with the branches tapped. Consider doubling the number of mites acceptable if most branches contain abundant natural predators such as lady beetles, minute pirate bugs, big-eyed bugs, predacious thrips, or predatory mites.

The minute pirate bug adult (Orius insidiosus) is only 3mm in size, but it is an excellent predator against oak spider mites. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

If many overwintering eggs are on the trunk & larger branches, then the use of dormant oil sprays will reduce future populations. This is especially true if the long-extended thick webbing is present. Targeting oil sprays within these webbed areas will greatly help with suppression. If active predators are abundant, then the continued use of summer oils will conserve beneficials. Some other reduced-risk miticides that are labeled for use against oak spider mites in residential & commercial landscapes include acequinocyl (Shuttle O), bifenazate (Floramite), spiromesifen (Forbid) & hexythiazox (Hexygon). Hexygon is a mite growth regulator & works as an ovicide & has activity against young mite larvae & nymphs. Hexagon will not control adult mites. Therefore, this material gives best results when mite populations are relatively small & still building.

Oak Lace Bugs (Corythucha arcuata)(~900 GDD = 1st generation nymphs): During the weeks of summer, the symptoms caused by oak lace bugs can be a concern to some landscapers & nurserymen. Often, the infestations are most pronounced on white oaks. From a distance, the stippling of leaves from this piecing-sucking insect can produce symptoms that are like those from oak spider mites or classic leaf scorch. Closer inspection determines the identity of the pest. Be certain to examine leaf undersides.

With an additional generation or two, by late August the leaf feeding symptoms can be more severe. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

With only the 1st generation active in early July, the feeding symptoms by the oak lace bugs are still mild. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Although the leaf discoloration of the foliage caused by oak lace bugs can be alarming, spraying is generally not considered to be necessary. Tall landscape oaks would require large spray volumes of insecticides to achieve controls. Some exceptions can be argued for valuable trees in high visibility areas, but usually action is not required. This pest primarily creates an aesthetic concern. It is doubtful the insects have significantly reduced the tree’s ability to store starches & sugars during much of the summer. Infested trees are often able to perform adequate photosynthesis before symptoms become severe. The plant health damage to large oaks in the landscape is usually minimal.

Oak lace bug eggs, 1st instar nymphs, & an egg laying adult. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Oak lace bugs & other species within the genus Corythucha feed on deciduous trees & overwinter as adults. Alternatively, lace bug species within the genus Stephanitis feed on broadleaf evergreens & overwinter as eggs. Distinguishing either genus from one another is relatively easy since adult lace bugs in the genus Corythucha have rectangular shaped wings, while species in the Stephanitis genus have wings that are oval shaped.

This Rhododendron lace bug is in the genus Stephanitis & the adults have rounded-off oval shaped wings. They feed on broadleaf evergreen hosts & overwinter as eggs inserted into the leaves. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Oak lace bugs are in the genus Corythucha & adults have squared-off rectangular wings. Lace bugs within this genus feed on deciduous hosts & overwinter as adults in secluded areas of the bark. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Interestingly, oak lace bugs have an egg laying pattern on leaf undersides that resemble a “miniature Stonehenge.” Look for a batch of 30 to 50 tiny black “spikes” arranged in a circular area of 3/4 inch diameter or less. These are sometimes incorrectly identified as excrement material but are the eggs of this insect. Overwintering adult females begin laying eggs in late spring after the oak leaves have expanded. In NJ, there are typically 3 or 4 generations per year with the final generation eggs being laid in late summer.

Oak lace bug eggs are inserted at leaf undersides & look like upright black colored bowling pins. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The photograph below shows a variety of signs that can be identified on leaf undersides. These include fecal spots, eggs, the 5 instars of the nymphs, and adults. This information may be considered esoteric by some, but it can be of value to determine the size of future generations by observing eggs. Also, if controls are desired, then targeting early nymph stages can enhance efficacy. As stated previously, often the symptoms do not become prominent until later into the summer after 2 or 3 generations have been feeding. If a key oak tree in a key location is consistently infested every year, then treatments are best when provided early in the season. A systemic (e.g., imidacloprid) applied to the roots of large trees may require at least 2-3 months before the xylem can translocate the material sufficiently throughout the canopy.