In this article:

- Impact & Biology

- Symptoms & Case Example: White pine blister rust

- Management

Where would we be without rusts? Rust diseases, to a plant pathologist, are anything but boring. In fact, this group of plant diseases contains some of the most destructive pathogens of vascular plants. Throughout history, rust epidemics have caused famine and wrecked the economies of entire civilizations. Important food and fiber crops affected by rust diseases include bean and soybean, grains (barley, corn, oat, and wheat), asparagus, cotton, pine, apple, and coffee (coffee rust is particularly troublesome in Guatemala right now). Rust diseases also affect a wide variety of ornamentals – landscape plants, greenhouse and nursery crops, Christmas trees – you name it.

A Sampling of Rust Diseases of Ornamental Plants

Ash rust (Puccinia sparganioides)

Aster rust (Coleosporium campanulae, Puccinia sp.)

Azalea/rhododendron (Chrysomyxa sp. and others)

Birch rust (Melampsoridium betulinum)

Carnation rust (Uromyces dianthi)

Chrysanthemum rust (Puccinia chrysanthemi)

Daylily rust (Puccinia hemerocallidis)

Fir-fern rust (Uredinopsis sp., Milesina sp.)

Fuchsia rust (Pucciniastrum epilobii)

Geranium rust (Puccinia pelargoni-zonalis)

Gymnosporangium rusts (cedar-apple, quince, hawthorn rusts)

Hemlock rust (Melampsora farlowii)

Hollyhock rust (Puccinia heterospora)

Iris rust (Puccinia iridis)

Pine-pine gall rust (Endocronartium harknessii)

Poinsettia rust (Uromyces euphorbiae)

Rose rust (Phragimidium mucronatum)

Snapdragon rust (Puccinia antirrhini)

Viola sp. (Puccinia viola)

White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola)

Willow leaf rust (Melampsora sp.)

The fungi that cause rust diseases are fascinating; many require more than one host to survive, and all produce, in succession, two or more different types of spores during the growing season. Rust fungi are related to the mushrooms you purchase in the supermarket, but the spores produced by these organisms are found in “rusty” (yellow to orange to brown) pustules on leaves, stems, needles, and fruit. Rust fungi are biotrophs: they do not grow in absence of a living host, and they tend to have a narrow host range.

Some rust fungi have a unique life history; those fungi that need more than one host plant to complete their life cycle (called alternate hosts) are heteroecious. Examples of heteroecious rust diseases include the Gymnosporangium rusts (for example, cedar-apple rust and quince rust), ash rust, and fuchsia rust. Alternatively, other rust fungi do not require more than one host plant to survive; these rust fungi are autoecious and include hollyhock rust, pine-pine gall rust, and geranium rust.

All rust fungi produce two types of spores: basidiospores, which result from genetic recombination, and teliospores (resting spores that also support the development of basidiospores). Many other rust fungi also produce additional spore types such as pycniospores, aeciospores, or urediniospores. Each of these spore types are found in a specialized pustule (fruiting structure) that develops on a given host during a certain point in the disease cycle. Those fungi that produce only teliospores and basidiospores are microcyclic. Those that produce all five spore types are macrocyclic. Those that produce fewer than five are…can you guess?…demicyclic. An excellent example of a demicyclic rust is cedar-apple rust: here, the urediniospore spore stage is missing.

Rust Fungus Spore Types and Pustules

Pycniospores produced in a pycnium

Aeciospores produced in an aecium

Urediniospores produced in a uredium

Teliospores produced in a telium

Basidiospores produced on the surface of a basidium

White Pine Blister: An example of rust disease that “has it all”

White pine blister rust is an example of a heteroecious, macrocyclic rust; the alternative hosts for this debilitating disease are 5-needle pines and species of Ribes (currant and gooseberry [Ribes subgenus Grossularia]). White pine was once dominant in northeast and north central forests; the pathogen, Cronartium ribicola, was introduced to the U.S. in 1898 on imported, diseased nursery stock. As the disease spread throughout pine growing regions, quarantines and a massive Ribes eradication program put in place to destroy the alternate host were only marginally effective. Fungicides are not useful for control of white pine blister rust; today, the disease is managed by planting (where available) disease resistant currants, gooseberries, and pines, pruning diseased pine branches, and not planting susceptible pines in “high hazard zones” (where environmental conditions are very conducive to disease). In New Jersey, regulatory restrictions are in place: planting of susceptible Ribes nigrum (blackcurrant) is only allowed under special permit, and movement of all species of Ribes and Grossularia to certain townships in Sussex, Passaic, and Morris counties is prohibited.

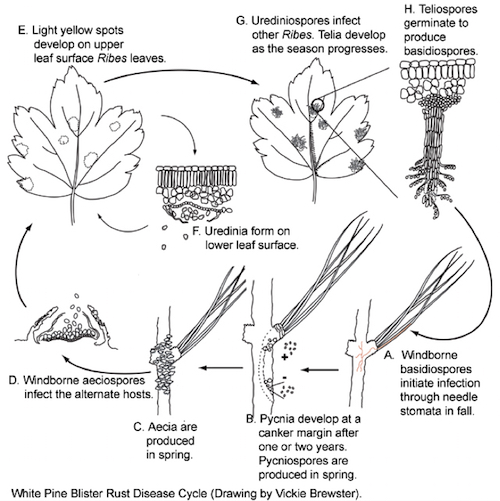

This disease cycle of white pine blister rust illustrates the relationship of alternate hosts to spores that are produced by the fungus in a set sequence.

Learning to “read” disease cycle diagrams can be very useful. In this cycle, teliospores produced on Ribes give rise in the fall to basidiospores (H) that infect pine needles through the stomates (A). Basidiospores germinate, penetrate the needle, and grow through to the branch where a swollen canker develops. In the spring of the second year (B), pycnia develop at the canker margin, and in the spring of the following year, aecia, at first covered by a white membrane, erupt through the bark at the same spot (C). These aecial “blisters” give the disease its name. Aeciospores produced in the aecia are windblown (D) back to the alternate host (Ribes), where yellow spots (E) develop. On the lower leaf surface, new pustules, called uredia, release urediniospores (F) that reinfect the same host (G). The urediniospore stage is called a “repeating” stage and serves to increase the amount of inoculum produced by the fungus. Later in the growing season, black telia form, and once again, basidiospores produced from the germinating teliospores are windblown back to pine.

These pustules (aecia) on white pine are filled with aeciospores. Spindle-shaped swellings develop into cankers that kill branches and ruin the quality of the wood for timber. Click image to enlarge.(Source: APSnet) Uredia with urediniospores produced on the lower leaf surface of Ribes. Click image to enlarge.

(Source: APSnet)

General Management of Rust Diseases

The best management strategies for rust diseases are preventive:

- Manage the moisture. Rust spores require moisture to germinate and infect host plants. Reducing humidity and leaf wetness (e.g., avoiding overhead irrigation, spacing plants to lower humidity and take advantage of prevailing winds, and using fans in greenhouses) will reduce the number of spores that successfully penetrate plant tissues.

- Use resistant plant materials. Where available, the use of resistant plants is the best strategy to disrupt the disease cycle.

- Inspect stock for symptoms and signs of disease. Scout! Purchase disease-free plants. Examine both existing and incoming stock for symptoms and signs of disease. Separate incoming stock from existing stock to prevent the introduction of pathogens and other pests.

- Remove the alternate host. Keep in mind that rusts are biotrophs. For heteroecious rusts, removal of the alternate host may help to disrupt the disease cycle. Rust spores are windblown, however, and may travel miles or hundreds of miles. For example, aeciospores can be disseminated up to 300 miles from pines affected by white pine blister rust. In most cases, it may be impossible to completely eradicate alternate host plants from the vicinity of economically important hosts, but this tactic may remove a good deal of inoculum.

- Practice good sanitation. In nurseries or greenhouses, carefully remove rust-infected leaves and other debris, and discard or isolate affected plants. Place diseased plant material in plastic bags to remove them from the greenhouse; destroy the refuse by burning, burying, or rapid-composting. At the end of the production cycle, clean up debris, and thoroughly clean and surface-disinfest greenhouse benches and propagation areas using a commercially available product for this purpose. Do not carry over plants exposed to rust to the next production cycle.

- Fungicides. Fungicides, used as preventives, can help disrupt the pathogen penetration process. In some crops, such as cereals, the cost of applying fungicides is prohibitive, and in other crops, they just don’t work. In landscapes, fungicides are not often recommended unless rust has been particularly severe on perennial plants for several years in a row. A combination of cultural management strategies and chemical controls is needed to effectively combat rust diseases in commercial settings. Keep in mind that rust fungi may develop resistance to certain classes of compounds, so rotating chemistries is important.

Fungicides labeled for rust on one or more ornamental crops include: single compounds: azoxystrobin, calcium polysulfide, captan, chlorothalonil, copper (pentahydrate, salts, soap), fenarimol, fludioxonil, fluoxastrobin, flutolanil, imazalil, kresoxim-methyl, mancozeb, myclobutanil, propiconazole, pyraclostrobin, sulfur, tebuconazole, thiophanate- methyl, triadimefon, trifloxystrobin, triflumizole, and ziram; combination products: boscalid + pyraclostrobin, chlorothalonil + propiconazole, chlorothalonil + thiophanate-methyl, copper hydroxide + mancozeb, copper oxychloride + basic copper sulfate, triadimefon + trifloxystrobin; biorational and biopesticide products: petroleum oil, essential oils (38%), neem oil, soybean oil, ammonium chlorides, potassium bicarbonate, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis, Reynoutria sachalinensis, Streptomyces lydicus.

Disclaimer: Read the pesticide label for application site, method, timing, host crop, and disease, and follow label directions. No endorsement of named products is intended, nor is criticism implied of similar products that are not mentioned.

Resources

For more information about white pine blister rust, visit the APSnet Plant Disease Lesson: White Pine Blister Rust, O. C. Maloy, 2003. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/Basidiomycetes/Pages/WhitePine.aspx

Regulatory information about the disease in New Jersey and other states is posted to the National Plant Board website: http://nationalplantboard.org/laws/index.html

All images are from the APSnet Plant Disease Lesson: White Pine Blister Rust, O. C. Maloy, 2003. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/Basidiomycetes/Pages/WhitePine.aspx