Many landscapers are familiar with the larger beneficial insects such as lady beetles, praying mantids, lacewings, and flower flies. Although common, parasitic wasps/flies (parasitoids) are examples of landscape beneficials that are typically less recognized because of their small size, and that magnification is needed for best viewing. Also many parasitoids feed unseen on the interior organs within their hosts. Although the majority of parasitoids are found in the two orders mentioned above (Hymenoptera & Diptera), there are more than 50 families that have been identified. Many of these insects do not have distinctive differences in general appearance & therefore attempting to ID the specific species or even family is not practicable for the landscaper or nursery grower. Learning about & being aware of the activity of these less observed but exceptionally important biological control organisms are photographed & reviewed in this blog.

An apparent parasitoid wasp inadvertently captured on the edge of a yellow sticky trap. Most of these adult wasps are exceptionally small & will often have a constricted waist & beaded antennae. The vast majority of observed landscape parasitoids will be wasp or fly species. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

PARASITOIDS: (Wasp & Fly Parasites)

Within the landscape, beneficial parasitic wasps or flies are called “parasitoids.” These parasites will cause the death of their hosts. Within the landscape, approximately 2/3rds are wasp species while 1/3rd are fly species. Unfortunately, parasitoids are often under-appreciated, since they can provide even better biological control than the larger predators. In many situations, parasitoids will give superior suppression of pests because they: (1) are more host-specific; (2) have a better searching ability; (3) work at lower pest densities; (4) require less food to complete development; (5) are better synchronized to their hosts’ life cycle, and (6) eliminate the hazards of host-seeking since eggs are laid in or on the host.

An adult female parasitoid within the family Aphidiidae or Braconidae is using her overpositor to insert an egg inside the body of an aphid host. (Photo Credit: Maryland Coop. Ext.)

Since parasitoid adults are usually significantly smaller and less stationary than many of our well-known landscape predators, they often go undetected by landscapers. Since parasitoid larvae often develop inside the host, it is difficult to monitor for and appraise their impact on a pest population. Monitoring for adults within the landscape may not be practical, although yellow sticky traps can be attempted. More effective field evaluations can be made by observing host symptoms such as the swelling of aphids into mummies, the darkening of soft scale insects, and the exit holes in armored scale insect waxy covers & exoskeletons of soft scales.

A parasitoid wasp within the genus Aphytis is often stated to be one of the most valuable for landscapers. Not only does the female lay eggs on scale pests for the wasp larvae to consume, it also performs host feeding. The female wasp wounds the armored scale by using her ovipositor to pierce through the waxy cover. While the scale bleeds to death, the wasps consumes the emerging blood. (Photo Credit: Maryland Coop. Ext.)

MONITORING: (What to Look For)

APHIDS: Aphids are the hosts of many biological control organisms including wasp parasitoids. An egg laid by the female wasp hatches inside the aphid with the larva consuming the internal structures of the host. Aphids containing parasitoids will typically become brown, swollen, and have a circular hole cut out of a hollowed body (these host symptoms are given the name “aphid mummies”). “Mummies” remain attached to stems and leaves for an extended period. Insecticide sprays can be avoided if many mummies are observed. If sprays are considered necessary, then soaps or oils or non-broad-spectrum insecticides can reduce detrimental impacts upon the parasitoids which are highly sensitive to many chemical sprays.

More than two dozen Black Bean aphids are present on the undersides of this leaf. At least four presently show evidence of having been parasitised by wasp parasitoids, but others will undoubtedly soon follow. The swollen, gray colored appearance is a good indicator that these aphid pests are no longer viable. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

All of the parasitised aphids on this leaf show the classic grey colored “mummies” appearance. The wasps pupate inside the empty carcass of each aphid & then emerged as adults after cutting out exit holes. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

It should be noted that specific pest and prey ratios needed to achieve satisfactory suppressions have been established for some pests, but many have not yet been determined through research. When beneficials are present, decisions to double the action thresholds for our key landscape pests have been recommended. Some biological control interactions are better understood than others, but it is a limitation to good field decision-making when evaluating the impact of beneficials.

A closer look at the parasitised Mellon aphids with a clear view of the smooth edged exit holes the adult wasps were required to make to escape from the carcass of the aphid. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

An even closer look (140x) at the parasitised aphid “mummies” having the cut-out exit holes & removed flaps created by the adult parasitoid wasps. Adjacent to each “mummy” are white aphid exoskeletons or cast skins. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

SCALES: It is understood that wasp parasitoids can provide the most effective biological controls for reducing scale pest populations. Research has shown this to be particularly true for the suppression of armored scale insects. The larvae of parasitoids feed on the adult scales beneath their protective waxy cover. It is impractical in the field to monitor the level of suppression by turning over the covers and examining individual insects with a hand lens. A more effective method is to observe characteristic circular holes in the scale covers that are created by emerging adult wasps. There is usually only one exit hole with each armored scale, but there may be several holes with each soft scale. If irregular tears are noticed in scale covers, then lady beetle predators were present. If holes have jagged edges, then possibly hyper-parasites were active.

These juniper scales show evidence of parasitoid wasp activities. With armored scales, there will usually be only a single exit hole per wax cover. The removed cover shows the partially consumed body of the actual scale insect. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The handful of calico scales show evidence of parasitoids with extensive exit holes within their exoskeletons. They are classified as soft scales & do not produce separate waxy covers as do the armored scales. Also unlike armored scales, there may be more than one exit hole per scale. Some of the individual scales shown above have 5 or 6 exit holes. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

When inspecting scale infestations, if many scale covers are seen having circular exit holes, then it is recommended that insecticide sprays not be made. The conservative use of control sprays is especially suggested if scale population densities are low, and no plant symptoms are evident. Numerous studies have indicated that the random or non-timed spraying of various broad-spectrum insecticides against armored scale populations in the field is often counterproductive. Often scale populations can be successfully suppressed by wasp parasitoids, but this ability is compromised, especially when poorly timed sprays are applied. All too often, improperly applied insecticides destroy beneficial parasitoids, have a limited impact on the scale populations, and may cause scale pest populations to increase.

An even closer look (100x) of juniper scales with most having exit holes from emerged adult wasp parasitoids. The edges of a couple of the exit holes appear jagged, possibly indicating the presence of hyper-parasites. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

To help reduce the destruction of beneficial parasitoids, the use of control sprays should be applied when plant damage symptoms are above aesthetic thresholds and beneficial populations are low. When warranted, a 3% horticultural oil spray is suggested during the late winter dormant season. However, do not expect this application to completely solve the scale problem. Additional 1-2% horticultural oil treatments should be applied when flying adult male scales emerge. Another summer oil spray should then be applied after crawler activity has ended. Therefore, two well-timed oil sprays are applied to each generation of scale insect (various armored scale species have between 1 to 3 generations per year). This control strategy allows parasitoids to maintain effectiveness. This alternate strategy is different than the more common recommendation that focuses on insecticides primarily being applied when scale crawlers emerge. However, both strategies can be successful.

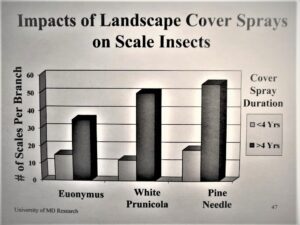

University of Maryland research study indicated that armored scales will increase at a landscape site overtime when broad spectrum cover sprays are applied. When cover sprays had a duration of more than 4 years then scale populations increased 3-4 times above the levels compared to sites where cover sprays were applied less than 4 years or not at all. (Graph Credit: University of Maryland Research)

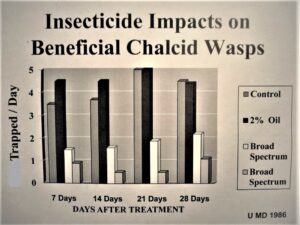

University of Maryland research study showed the detrimental impacts the use of broad spectrum insecticides had on Chalcid wasp parasitoids in the landscape. Results showed over a 4 week period of time, that the broad spectrum insecticides reduced Chalcid wasps between 50-90% compared to the effects from 2% horticultural oil treatments. (Graph Credit: University of Maryland Research)

Additional Parasitoid Examples:

A series of photographic examples show parasitoids that have successfully attacked the larva, eggs, and pupa of different caterpillar pests often encountered in the landscape. The photo examples with caption descriptions include: 1-Braconid wasps (Cotesia congregates) that have parasitized a tobacco hornworm caterpillar; 2-Ooencyrthus kuvanae wasps that have parasitized a spongy moth caterpillar egg mass; 3-Tachinid fly species that parasitized a bagworm caterpillar pupa.

1a-The tobacco hornworm ( Manduca sexta) & tomato hornworm (Manduca quinquemaculata), are significant pests that many gardeners are familiar with. A small braconid wasp, Cotesia congregatus is one of the most common parasitoids found parasitising this caterpillar. The wasp larvae feed inside the body digesting the interior structures. The photo shows white cocoons protruding from the body of the tobacco hornworm after wasp larvae emerged to pupate. After adult wasps emerge from the cocoons, they will search for other hornworms to parasitize. This hornworm caterpillar is now a member of the “walking dead.” (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

1b- As would be expected, because of the large size of the larva, the adult moth of this apparent tomato hornworm is also exceptionally large. The wingspan of extended wings can reach 5 inches. These robust moths are remarkably agile flyers. They have the ability to hover like hummingbirds. The parasitised larva shown in the first photograph above would not have successfully pupated & reached this adult stage. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

2a-A tiny parasitoid wasp of spongy moth (previously called gypsy moth) egg masses is Ooencyrtus kuvanae. This specialized wasp parasitoid was introduced into the United States many decades ago & can have 3 generations per year. The adult wasp inserts an egg into the egg of a spongy moth. The average size spongy moth egg mass contains between 400 to 600 eggs.

2b-The small, round holes evenly distributed within this spongy moth egg mass were created by the adult parasitoid wasps as they emerged. The spongy moth eggs are laid in multiple layers within the mass. These tiny wasps have short ovipositors & can only reach & lay eggs in the upper layers of the mass. Therefore, no more than 20-30% of the spongy moth eggs within a mass can be successfully parasitised. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

3a-Tachinid flies within the family Tachinidae are the most important group of parasitoid flies. Various species will attack the larval stages of some of our landscape caterpillar pests. The above photo shows the recent pupal emergence of an adult male bagworm moth (black moth to the right of center). At the upper left corner of photo is a Tachinid fly laying an egg within the bagworm still in the larval or pupal stage. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

3b-Tachinid fly adult emergence hole in the body of the incomplete development of the pupal stage of a bagworm caterpillar. The presence of this parasitoid fly would have remained hidden & undetected without the opening-up of the protective bagworm sack. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Reference: Syllabus of the 1997 Advanced Landscape Plant IPM Short Course, Volume III; John Davidson, Dept. of Entomology, Univ. of Maryland