Azalea Lace Bugs (802-1029 GDD = 3rd generation): The third generation of this pest will be in full swing for much of NJ by the end of the month. Look for the presence of nymphs (spiny, black), adults (larger, lacy wings), fecal spots (brown, shiny spots) on the underside of leaves, and stippling (feeding damage from nymphs and adults) on the leaves. Remember that the yellow stippling damage persists on the leaves until they are dropped. Look for the presence of actively feeding lace bug nymphs or adults before treating plants.

Azalea lace bug stippling symptoms on Azalea leaves. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Azalea leaf undersides with frass spots & egg laying along mid-rib. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

When found, use horticultural oil (only if a spray can contact the back of the leaves), or acephate (Orthene) if the shrub is too dense to allow effective use of oil. Imidacloprid (Merit) applied to soils now may require 1-2 weeks before they begin to control this second generation or the beginning of the third generation (longer if soils are dry). Chlorantraniliprole is a reduced-risk insecticide that can be effective against lace bugs. Remember that stressed azaleas in full sun are more prone to lace bugs. Also, & more importantly, predators will be fewer in full-sun locations.

Azalea lace bug adult with oval shaped wings. Lace bug species having oval shaped wings will only feed on broad-leaf evergreens. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The Landscape Pest Notes for Late June 2023 in addition to the azalea lace bugs also includes information & photographs of oak spider mites, two-spotted spider mites, pine spittlebugs, mimosa webworms, various soft scales, white prunicola scales, red-headed flea beetles & tree species prone to mid-season leaf drop.

Azalea Lace Bugs & Cultural Controls: 1) When populations are low and plants are small, simply crush the bugs by pressing leaf parts together between the thumb and forefinger. 2) Dislodge nymphs (no wings) with a strong jet spray of water (syringing). Many may not be capable of crawling back to suitable leaves to feed upon and will soon die. 3) Azaleas are rarely excessively damaged by lace bugs when watered sufficiently and planted in shady areas of the landscape. Lace bugs thrive in sunny locations where predators are less numerous. 4) There are several beneficial insects such as spiders, lacewings, assassin bugs, and the minute pirate bug that can effectively reduce lace bug populations. Encourage and conserve these predators by avoiding unnecessary cover sprays with broad-spectrum insecticides. Syringing with a jet stream of water may allow time for beneficials to build up and keep damage to a minimum until significant predators arrive.

Close-up of the mouthparts of the green lacewing predator. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Oak Spider Mites (802-1265 GDD = 1st generation): The infestation and damage levels by most of our “warm season” spider mites typically become active during June and continue throughout the summer months. When monitoring oaks, look for the characteristic bronze discoloration on the upper leaf surfaces of mostly red oak group species (can also occasionally be found feeding on birch, chestnut, beech, elm, and hickory). Eggs are generally deposited on upper leaf surfaces, along the mid-vein. Multiple generations occur with peak populations in mid to late summer. After egg hatch occurs in the late spring (e.g., June), controls should be applied before large populations build up by mid-summer. Over-wintering eggs can be controlled with dormant horticultural oil. Elongated silk webbing may protect overwintering egg masses during very heavy infestations. Areas of the trunk and branches can have the appearance of rusty fiberglass. This silk webbing may be difficult to penetrate with horticultural oils. Some of the reduced-risk miticides labeled for spider mites include spiromesifen, bifenazate, & acequinocyl.

Oak spider mite stippling symptoms on upper surface of oak leaf. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Oak spider mite stippling symptoms along with cast skins & egg shells. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Spider Mites on Winged Euonymus: During the hot summer months, two-spotted spider mites can cause significant damage to winged euonymus/burning bush (Euonymus alatus). Infestations build up during June on the lower, inner leaves, causing a pale-white discoloration. With high populations, foliage throughout the plant turns a reddish-brown coloration by July/August. Note that these same symptoms can be similar to plants experiencing physiological stress (e.g., drought stress). When monitoring these plants, always check for spider mite presence by using a beating tray and a magnifier (10x-15x). Make sure live mites are present before making treatments! Within residential or commercial landscapes, damage thresholds are not reached until more than 10% of plant foliage shows symptoms. When beating tray tests contain more than 15 spider mites, then treatments may be recommended.

Winged Euonymus defoliation from two-spotted spider mites. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Early detection of two-spotted mites on the burning bush is critical to prevent discoloration and premature defoliation. Plants known to have had a history of this pest should be monitored at least every two weeks throughout the summer months. Proper timing of chemical controls should give excellent results. The many-labeled contact miticides will usually work well when coverage is complete. Horticultural oil can be effective if used cautiously (be careful of drought-stressed plants and hot/humid weather). Target the spray treatments to the undersides of the leaves.

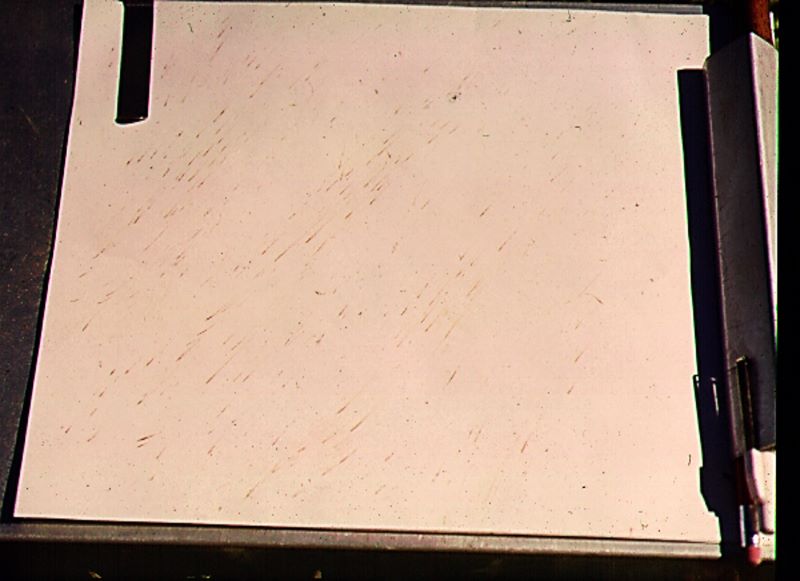

The white colored beating tray is a useful tool to quickly determine population levels of spider mites. When mite blood streaks exceed 15, then symptoms may become too high. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Two-Spotted Spider Mite (Resistance Management): With the eventual onset of hot and dry weather the build-up of two-spotted spider mites will soon become apparent on burning bush, rose, forsythia, and many perennial plants. This mite species probably produces the greatest amount of silk webbing compared to any of the other landscape mites. However, it would be a mistake to wait until webbing becomes obvious before any action is taken. Usually by late May to early June the overwintering adults begin to move upward from the underlying duff onto their host plant (Remember that a dormant oil spray will not effectively impact the concealed adults if applied during the late winter or early spring periods). This species performs best in hot and dry environments. When daily high temperatures routinely exceed 85°F. then spruce spider mites shut down their activity while the 2-spotted spider mites greatly accelerate their development.

The “architectural beauty” of the webbing created by two-spotted spider mites on summer mum plants. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

During the summer months, two-spotted spider mites will typically undergo 10 to 15 generations per year (i.e., the spruce spider mite usually has between 7 to 10 generations per year). Miticide resistance management is particularly important because of the large number of generations that two-spotted spider mites experience. If the same class of miticide with a similar mode of action is used continuously over time at the same location, then resistance to that material will eventually occur. There will always be a small percentage of a given population of mites that have a natural genetic resistance to a specific miticide. For example, they may be able to metabolize the active ingredient or produce enzymes that can rapidly destroy the active ingredient. Or perhaps some individuals can develop exoskeletons that can effectively block/repel the penetration of the active ingredient.

Two-spotted spider mites & eggs beneath leaf. Recently laid eggs still have a clear appearance. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

When the same materials with similar modes of action are used repeatedly at a particular site, then the percentage of the mite population having this unique resistance ability will increase with each generation. As a result, it is especially important to routinely throw “genetic curveballs” when attempting to manage two-spotted spider mite infestations. As a general rule of thumb, a good resistance management practice is to rotate to a new class of miticide having a different mode of action after every 2 to 3 applications. Many insecticides/miticides now have resistance management requirements stated on the label. These requirements need to be understood and followed.

Pine Spittlebugs: The native spittlebug attacks nearly all of our common pines, as well as Norway, white and red spruces, balsam fir, larch, eastern hemlock, and Douglas fir. Several species of spittlebugs can be found feeding on various hosts, including deciduous plants. Nymphs are covered with frothy honeydew called spittle. Most species have only a single generation & overwinter as eggs on bark cracks. They are mostly black in color with a white abdomen and can be found under spittle on twigs in May and June. Inspect for adults feeding in the same locations in July and August without the spittle covering. Adults are about ¼ inch long and are mostly tan in color with whitish bands on the wings. Both adults and nymphs suck sap from the phloem vessels of twigs.

The larvae of pine spittlebugs will form a frothing mass of air & sap as protection when feeding. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Pine spittlebug feeding on false-cypress foliage. Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Damage is usually not serious with light infestations and chemical controls are not warranted. When most terminal shoots contain more than one spittle mass, then residual insecticides may be warranted. This is especially true when some species release toxins that cause leaf stunting & twig decline. On pines, feeding puncture wounds can provide an opening to invasion by plant diseases.

On small pines, spittlebug populations may be manually removed. Adults are more active than nymphs and may require an insect net to effectively keep them from twigs. If necessary, spray spittle masses with a residual insecticide in May. There are a handful of pyrethroids that are labeled for use against spittlebugs.

Mimosa Webworms (880 GDD = 1ST Generation Larvae Hatch): This tent/web-forming caterpillar becomes active in much of NJ during the 2nd half of June. They feed on mimosa and honey locust (especially the thornless varieties of honey locusts such as ‘Moraine’). The young caterpillars initially web leaflets together and then expand the web to include several branches as they grow. Older larvae consume foliage. The webbed foliage is unsightly, giving trees an ugly grey/brown appearance. The adults have the habit of laying their eggs on the old webs, so the second generation (due in early August) magnifies the damage, and large populations may defoliate the tree.

Mimosa webworm cocoons overwinter under bark flaps on tree trunk. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Mimosa webworm adult moths (1st-generation) emerge from pupation skins during mid-June in most of NJ. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Since there may be many webs in one tree, hand pulling/pruning is usually ineffective. Monitor for the first signs of webbing of the second generation (1800-2100 GDD; when Hydrangea paniculata is blooming) and apply B.t. on small larvae. Spinosad (Conserve) & chlorantraniliprole may also be used with reduced impact on beneficials and non-target organisms. Residual pesticides, such as Orthene, Scimitar/Battle, Tempo 2, Mavrik, or Talstar may be used to control older larvae (be sure to drench foliage thoroughly). The four pyrethroids listed above may cause a spider mite flare-up following application, so a miticide may become necessary.

Mimosa webworm caterpillars (1st-generation) form extensive webbing at leaf terminals during late June & July. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Soft Scale Species Controls (June & July): Compared to armored scales, the soft scales are relatively easy to suppress with either contact sprays or systemic treatments. Some of the common landscape soft-scale species include Calico, Fletcher, Wax, Terrapin, Cottony Maple, Lecanium, Cottony Taxus, Pine Tortoise, Striped Pine, and Spruce Bud. Although large soft-scale adult females are more difficult to control, crawlers & immature nymphs are highly vulnerable to insecticide sprays when good coverage is achieved during June & July.

Fletcher scale is a soft scale & is shown feeding on an arborvitae plant. This scale species has crawlers that emerge in late June & early July. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Fletcher scale female with hundreds of unhatched eggs. Some soft scale species can have 1 to 2 thousand eggs per female. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

There are numerous windows of control when applying sprays or systemic treatments against soft scales. (1) The best window for control when using spray treatments is toward the crawler emergence period. With only two major exceptions (Magnolia & Tuliptree scales), all other soft scale species produce crawlers during the months of June or July. Although scale crawlers are only 2 to 3 times the size of spider mites, they are usually clearly visible without magnification. Most crawlers have yellowish or reddish coloration. (2) Sprays can also be successfully targeted against the settled 1st instar nymph stage feeding on foliage or bark during the growing season. Achieving adequate coverage of foliage is the major challenge with large deciduous shade trees since the settled nymphs feed on the undersides of leaves along major veins. (3) In addition, dormant oil treatments can be applied in the late fall or early spring to the over-wintering 2nd instar nymphs on deciduous hosts. These nymphs have black or brown coloration and are considerably larger than the crawlers and 1st instar nymphs. They can be observed in clusters on the bark of twigs, branches, or trunks. (4) Finally, since soft scales are vascular feeders (phloem or xylem), root-absorbed systemic insecticides such as imidacloprid (Merit) or dinotefuran (Safari) have provided better than 90% control rates. Root systemic treatments can be applied as a drench or by soil injection at any time during the year as long as the ground is not frozen. Fall or spring applications are most typical. Having adequate soil moisture is key to ensuring success when applying root systemic treatments. (Note: None of the neonicotinoids will be labeled for use within NJ residential landscapes after October 2023).

Indian wax scale adults are difficult to control because of their thick, waxy exoskeleton. Controls are best achieved in July against immatures. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Indian wax scale immature “cameo” stage in July is a good time to achieve controls against this soft scale. (Photo Credit: Cornell University)

White Prunicola Scales (707-1151 GDD): The crawlers hatch and become active in June in many areas of the state. This is the first of three generations. It attacks flowering cherries, and plants in Prunus, as well as lilac and privet. The white prunicola scale is also commonly found feeding at the base of Ilex plants within containers in nurseries. All stages of this armored scale feed in plant cells on twigs & branches. Heavy infestations can cause leaf yellowing & premature defoliation followed by branch dieback.

White prunicola scale males with waxy filaments completely cover the female scales. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The white prunicola scale males are elliptical in shape while the females are larger & circular. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

This scale species is particularly difficult to control because the crawler generations can continue to emerge over prolonged periods throughout the season. The second and third generations occur during the mid and late-summer periods. Soaps and oils (1%), targeting the branches and trunks will control crawlers when seen. The crawlers have a distinctive salmon color. Plan a dormant oil application for late winter next year. The systemic dinotefuran is highly effective against armored scales. (Note: None of the neonicotinoids will be labeled for use within NJ residential landscapes after October 2023).

Within container nurseries, the white prunicola scales commonly occur at the base of Ilex plants. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Red-headed Flea Beetles (550-750 GDD = 1st generation): The first emergence of the adult red-headed flea beetle (Systena frontalis) is typically observed in southern NJ during early June. This insect has been a major pest at numerous NJ nurseries during the past 15+ years. Primarily a concern with container crops in nurseries, it has an extensive host range. The foliage damage to plants from this 0.2-0.25-inch adult beetle can become extreme.

Red-headed flea beetle feeding caused severe damage to sedum plant. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Commonly observed nursery hosts of the adult flea beetle include Ithea, Salvia, Buddleia, Veronica, Coreopsis, Weigela, Hydrangea, Sedum, & Rudbeckia to name only a few. This flea beetle species typically has a prominent reddish head with the thorax & abdomen being a distinctive shiny black. The enlarged femur at the hind legs enables the flea beetle to rapidly “hop” when disturbed. In New Jersey, there are usually 2 or possibly 3 generations during the season and therefore feeding damage can occur from mid-June through much of September. Overwintering in the egg stage, grubs hatch during the 2nd half of May. First-generation adult emergence occurs about a month later (550-750 GDD) with the additional 2 generations producing the potential continued feeding damage that can span several months.

Extensive red-headed flea beetle feeding damage to weigela leaves. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Adult red-headed flea beetle feeding symptoms can be variable depending on crop leaf types. Feeding on thinner leaves tends to produce skeletonized symptoms or may even result in a shredded appearance. With thick, fleshy leaf types (e.g., Sedum), the feeding symptoms can mimic the light-colored linear patterns seen from leaf miners.

Red-headed flea beetle adults are less than 1/4-inch in size. They hop away rapidly when disturbed. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Although chemical controls against the feeding adult can be effective, nursery growers attempting to protect crops often require repeat treatment applications. The use of neonicotinoids such as imidacloprid (Marathon) & dinotefuran (Safari) can provide residual preventative controls, but experience has shown it may also be necessary to apply knockdown rescue treatments such as pyrethroids (i.e., cyfluthrin (Decathlon) & lambda-cyhalothrin (Scimitar)) or carbaryl (Sevin). Some immature larvae (5-10 mm) may be found in the container media feeding on roots, but typically cause insignificant damage. Controls targeting adults are most effective, but controlling larvae can also have some significant impact.

Larva of red-headed flea beetle feeds on roots, but cause little damage. (Photo Credit: New Hampshire Coop. Ext.)

Mid-Season Leaf Drop: When the leaves of large shade trees drop during mid-season, it typically causes alarm to concerned homeowners/clients. With the ground littered with spent foliage, the conclusion often is that “their favorite shade tree is dying!” Linden, birch, and sycamore trees are often most susceptible to mid-season leaf drops. In a majority of cases, this is a normal physiological growth habit for these species. The trees commonly drop foliage in mid-season to reduce leaf surface area and subsequent water loss. This leaf-shedding ability is especially important during typical summer droughts or when water availability in soils is limited.

Gray birch tree shedding leaves during a summer drought. Unless the drought is extensive, the tree health is usually not threatened. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

River birch trees dropping leaves during a summer dry period at this nursery. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

To add to the potential concern & confusion regarding the health of the tree, after water does eventually become available to the roots through rainfall or irrigation the tree has an increased leaf drop. The tree was preparing to excise some of the leaves when the extra weight of the water accelerated the process. The tree species mentioned above will often grow an exorbitant number of leaves during the spring months when moisture levels are plentiful. Therefore, neither tree health nor tree growth is usually affected unless the drought extends over a long period.

Reference: Managing Insects & Mites on Woody Plants: an IPM Approach (3rd Edition); John A. Davidson, Ph.D and Michael J. Raupp, Ph.D; Dept. of Entomology, Univ. of Maryland.