Even though much of New Jersey has had wet weather recently, which is more favorable to Pythium and Phytophthora development, Rhizoctonia root rot has been reported over the past few weeks in a number of crops. Rhizoctonia root rot, caused by Rhizoctonia solani, is an important soil-borne fungal pathogen with a very large host range. The pathogen can survive saprophytically on living or dead plant material (organic matter) or as sclerotia in the soil (for more than 3 years). Disease development is favored by warm temperatures, dry (or very well drained) soils and stressed plants. Symptoms of Rhizoctonia root rot may begin as stunted plant growth (with poor root systems) with the appearance of brown lesions at the base of the stem causing wilting with lesions eventually girdling the stem and killing the infected plant. Rhizoctonia root rot infections only extend about an inch above the soil surface (Figure 1), unlike Phytophthora blight infection which can extend much farther up the stem.

Figure 1. Rhizoctonia root rot in tomato. Note the infections only extend about an inch above the soil surface.

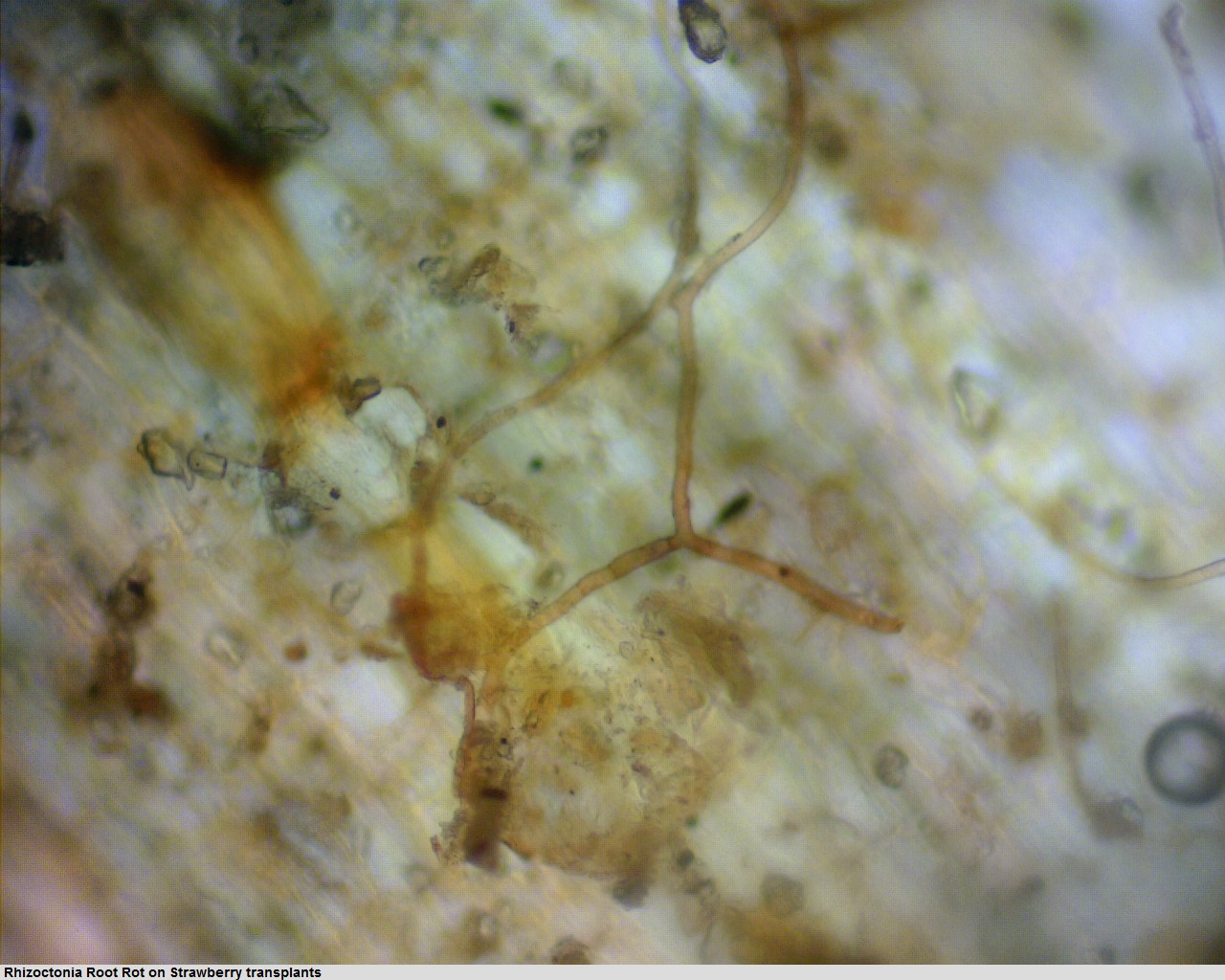

Additionally, in root systems infected by Rhizoctonia, the outer cortex of the root system won’t slough off, like it does with Pythium root rot infections. Under ideal conditions, the mycelium of the fungus growing can be seen with a 10x hand lens growing along the root surface (Figure 2). Rhizoctonia produces distinct, brown hyphae that almost always branches at nearly 90 degree angles and is a diagnostic feature of the fungus (Figure 3). Rhizoctonia root rot often shows up in transplant production when plug trays are held on the dry side for extended periods, often when growers reduce water to control transplant growth. Infected transplants may not show symptoms until after they are set in the field. Infected transplants or plants infected shortly after transplanting often remain short and stunted with poor root systems compared to healthy plants. This most often occurs when the top of transplant plug has not been sufficiently covered over by soil, the lack of water used in setting the transplant, or when drip irrigation systems have not been hooked up and the soilless media becomes excessively dry for a period of time after transplanting.

Figure 2. Rhizoctonia growing along the surface of an infected strawberry root.

Figure 3. Distinct brown hyphae of Rhizoctonia root rot. Note the 90 degree angle in the branching of the hyphae.

Control of Rhizoctonia root rot begins with recognizing its symptoms, so as not to confuse it with other soil-borne diseases, proper watering and irrigation pre-, at-, and post-transplanting, and preventative fungicide control measures post transplanting. For more information on the control of Rhizoctonia root by crop please see the 2024/2025 Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations Guide.