Too often, landscape plant managers ignore or confuse beneficial organisms with insect pests and inappropriately apply control materials. This is especially the case with the larvae or immature stages of beneficial insects. An observant and knowledgeable IPM scout needs to learn how to recognize and conserve these “good guys,” so they are not needlessly destroyed. Remember, “we must look before we shoot,” when spraying pesticides and take advantage of natural pest control that works for free!

Home entrance walkway with diverse plantings of numerous species. An ideal setting to attract many beneficial insects. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The classical definition of biological control is the use of natural enemies to control insect pests. These natural enemies include predators, parasitoids, and pathogens. Pathogens are microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoan, and nematodes) that kill pests. Parasitoids are parasites that kill their hosts by their feeding activities. Most parasitoids of landscape pests are wasps and flies. This blog will discuss some of the more valuable ornamental landscape predators.

Over one hundred praying mantids can emerge from a typical sized egg case (ootheca). Although excellent predators, praying mantids are NOT considered to be valuable in the home landscape. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

PREDATORS

The most common insect predators typically encountered in the urban landscape are lady beetles, lacewings, and flower flies. These insects are usually, but not always, larger than their prey. They are active and fast-moving since they must hunt and capture other insects to survive. Each of the three predator types listed above must consume a lot of prey to complete their life cycles. With some species, hundreds of individual prey hosts must be consumed before the development of the predator can be completed. Although technically not insects, another common but excellent “backyard beneficial” are predatory mites species contained within the family Phytoseiidae. These tiny but “mighty” predacious mites will be covered in a future blog.

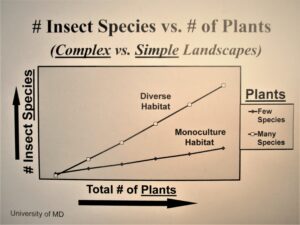

Theorized graph indicating relative numbers of insect species observed at simple vs. complex landscapes. (Univ. of MD research)

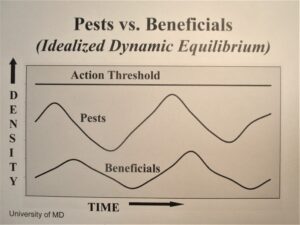

Theorized graph indicating how pest & beneficial insects may wax & wane over time at a site. An idealized dynamic equilibrium is achieved when pests are kept below action thresholds. (Univ. of MD research)

Ladybird Beetles (family Coccinellidae)

Ladybird beetles have been incorrectly called ladybugs by so many, for so long, that this common name has become accepted, except by entomologists. We have all been able to recognize the adult stage since we were kids, but there are still too many of us who cannot identify the larva stage of the ladybird beetle. The larvae are 1/8” to ¼” long and are elongated in shape. The segmented body tapers from the front to the back end with many body segments containing spines. The color is variable, often showing bright yellow to orange markings, with a black background. The larger and more brightly colored larvae are those species that feed most heavily upon aphids. Alternatively, the smaller, darker, and less colorful larvae are species that feed primarily on scale insects.

Adult ladybird beetle species attempting to lift & get under the tuliptree scale & feed on the soft underbelly. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Ladybird beetle larvae are usually more voracious predators than during the adult stages. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The eggs can be up to 1/8” long, are elongate oval, and yellow or white. Easily observed by those with a keen eye, they are mostly seen as yellow eggs laid on end in clusters of 10 to 20. Single, white eggs are laid by lady beetle species that prey upon scales and mites.

Ladybird beetle species have a complete metamorphosis & all stages are shown. After the yellow eggs hatch the remaining egg shells will be white in color. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The most common prey of ladybird beetles are aphids, scale insects, and spider mites. Since the larvae feed most voraciously on prey, it is important to be able to identify this predator during the immature stage. Research has shown 3 to 4 larvae controlling over 300 aphids per 2-foot branch terminals on apple trees. However, when all prey is consumed, ladybird beetle larvae may turn cannibalistic and devour one another. Although this behavior limits some potential benefits, it ensures that some individuals will have enough prey to develop to become adults and reproduce to create the next generation. If there is not enough prey to supply another generation, the second-generation adults will then leave that area without laying eggs. Once autumn temperatures consistently drop below 65°F. most lady beetle adults will stop their activity and search for protected overwintering sites.

The ant drinks from a pool of honeydew that exuded from the tuliptree scale located above. Ants will protect honeydew producers & will fight off predators that attempt to feed on them. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Ladybird beetle larva covered with wax feeding on tuliptree scales. The wax attempts to mimic the appearance of mealybugs in order to avoid attack from ants. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Do not always expect outstanding results by purchasing lady beetles from catalogs (often collected in California) and releasing them in the Northeast to provide pest control for landscape ornamentals. They may not find the proper conditions for feeding and egg production, and therefore, will provide little to no value. Plus, they typically fly away upon release! Simply conserving the activity of those naturally present can provide meaningful pest control for outdoor ornamental plants.

Lacewings (family Chrysopidae)

The larvae of green lacewing insects are some of the most useful beneficials found in the landscape. These voracious creatures are sometimes called aphid-lions and have been described as the “psychopaths of the insect world,” because they are truly “killing machines.” The larvae are 1/8” to 3/8” in length, have a flattened elongated shape, and are drab brown to gray. They have large, deadly fang-like mandibles that are used to impale their victims to suck out body fluids.

Green Lacewing larvae are commonly called aphid-lions, but have also been known to feed on a 1000 spider mites per day. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Green lacewings can often be found attacking prey larger than themselves and appear to have insatiable appetites. One larva, for example, may eat 1,000 spider mites a day for 15 days. Observations in apple orchards have shown that lacewing larvae have controlled apple aphids at a ratio of 1 to 70, and at rates of up to 60 aphids per hour (Note that if this ratio reaches a 1 to 150 level, the predator is overwhelmed, and suppression is not achieved). Lacewings prefer mostly soft-bodied insects such as mealybugs, scale insects, whitefly, and the eggs of caterpillars and thrips.

Close-up of the deadly fangs of the lacewing larva. They can easily puncture aphids & other soft bodied insects & then rapidly suck out body fluids. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Green lacewing eggs are oval, and white and are located at the end of 1/4 inch long silken threads in groups or individually. The eggs are placed on the ends of the stalks to reduce cannibalism from siblings. Eggs hatch after 6 to 14 days. Since this egg-laying appearance is unique within the landscape, they are easily identified when monitoring. After egg hatching the larvae feed for 2 to 3 weeks before they spin whitish, pea-sized cocoons and pupate while attached to a leaf. The last generation of the season will overwinter as cocoons in the pupal stage.

Dozens of 1st instar lacewing larvae are hatching from eggs located at the end of 1/4 inch silken threads. Honeydew from aphids above rained downed & caused the eggs to clump together. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The adults of lacewings are weak flyers with fragile bodies and are not usually considered to be effective predators. The more common lacewing species in the landscape have greenish bodies, heavily veined wings, and are ½” in length. ‘They primarily feed on honeydew, nectar, pollen, and aphids. Lacewing adults can live for 3 to 5 weeks. Although not a great predator, the adult females of some species do require aphids as food to stimulate egg production.

Pupation cocoon of green lacewing species with cut-out flap indicating successful emergence of the adult. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The delicate green lacewing adults are weak flyers & are most active during the hours of dawn & dusk. Larvae are far more voracious predators than adults. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Flower Flies (family Syrphidae)

The flower fly / hover fly (or syrphid fly) is an insect that many landscapers have seen but incorrectly identified as a type of wasp or bee. Their hovering flight and yellow to orange band markings on the abdomen help cause this misidentification. Although these beneficial insects are predacious only in the larval stage, they are another important group of predators that rival the abilities of lady beetles and lacewings. The larvae of flower flies are unknown allies to many landscape plant managers. It is rare not to find at least a few of these 1/8” to ¼’ long tan or greenish maggots feeding within an aphid colony. The larvae also have black markings on their bodies and have pointed anterior and blunt posterior ends.

The adult flower fly mimics the appearance of yellow jacket wasps. Although the adults are not predators they can be valuable pollinators. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

These larvae will quietly meander over the plant surface methodically grasping one aphid after another. Once this predator spears an aphid with its pointed jaws (i.e., their mouthparts consist of 2 retractable hooks), it raises the prey into the air and sucks out the fluid contents. A flower fly can destroy aphids in this manner at a rate of one per minute over an extended period. It is also significant to note that they are usually the major predator in the fall season since they can function at cooler temperatures than either the lady beetles or lacewings. The flower fly larvae also prey upon leafhoppers, scales, mealybugs, and thrips.

Flower fly larvae are fly maggots & will often go undetected as they feed on prey. The dark colored markings on their bodies are clearly apparent. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

The adults closely mimic the flight pattern of hummingbirds as they hover over flower heads. The adults-only feed upon pollen and nectar and are themselves valuable pollinators. Females require pollen from flowers or weeds before they can produce eggs. Adults often require the presence of a couple of dozen aphids per leaf before egg-laying will be triggered. The eggs of flower flies are flat, 1/8” long, whitish, and finely divided. These elongated eggs are laid individually and attached lengthwise on leaf surfaces among groups of aphids.

Flower fly adult captured in mid-flight. Adults will hover in space as they search for potential flower pollen or prey to lay eggs. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Flower fly eggs are white & elongated. A bloated parasitised aphid & aphid white cast skins are shown nearby. (Photo Credit: Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Coop. Ext.)

Reference: Syllabus of the 1997 Advanced Landscape Plant IPM Short Course, Volume III; John Davidson, Dept. of Entomology, Univ. of Maryland