The fungus Epichloë typhina, several other species of Epichloë, and the closely related asexual species of form genus Neotyphodium, are symbionts of cool-season grasses, which are known as “endophytes.”

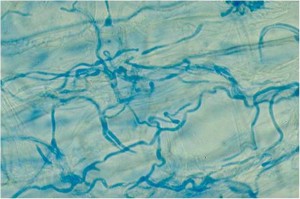

Intercellular hyphae of the Neotyphodium endophyte. Photo: Dr. Philip Halisky, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

Endophytic fungi enter seeds via an infected mother plant and are disseminated with that seed. As the infected seeds germinate, the fungus grows between cells into the crown and up the leaf sheaths of the emerging seedlings. Epichloë and Neotyphodium fungal infections persist for the life of the plant and have little or no negative effects on their hosts. Quite to the contrary, the positive benefits of endophyte-infection in cool season turfgrasses are well known.

Endophyte-enhanced ryegrass resists billbug feeding in turf trial. Photo: Dr. Philip Halisky, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

Endophyte-infected grasses – fescues and ryegrasses carry the infections, while bluegrasses and bentgrasses do not – are more drought tolerant, have more root biomass, fix nitrogen better and are generally more vigorous than their uninfected counterparts. These fungi also produce a variety of fungal alkaloids that deter the feeding of grazing animals including several leaf-feeding insect pests, and as such, have become important parts of turfgrass integrated pest management systems.

In certain endophyte species, the initiation of a seed head in an infected grass plant can trigger the fungus into a sexual reproductive cycle. In this rare developmental stage, the fungus produces a spore forming stroma on the emerging inflorescence that stops the development of the seed head. When this happens, the disease is termed “choke disease.” Infected plants look like little green Q-tips™ in the turf canopy.

Don’t let the possibility of a choke outbreak keep you from using endophyte-infected grasses in your pest management program. Unless you are in the business of seed production, choke is just another wonder of nature that will simply mow off in another pass or two.

Click here for more information on commercially available turfgrass varieties that are endophyte-infected.